A Very Brief History of Karabakh-Artsakh

Available at: Free Download

For High Resolution images the book is also available from the publisher and bookshops.

24×16.5 cm, 48 pp., with47 with colour images and maps.

Publisher: Antares, Armenia, 2023

ISBN 978-9939-98-052-2

Language: English

“`The Last Supper from manuscript

N-316 in Matenadaran, Yerevan.

Miniature from Karabakh,

during the 13th century.

The Armenian inscription read:

Guest room.

Jesus Christ

The Apostles

Judas,

who had got his

morsel and

left

Author’s other books published in English

- Historic Maps of Armenia. The cartographic Heritage, I.B. Tauris London and New York, 2004.

- Countries South of the Caucasus in Medieval Maps; Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan, Gomidas Institute, London, 2007.

- The Invention of History: Azerbaijan, Armenia and the showcasing of Imagination, Gomidas Institute, London, 2009 and 2010.

- Clash of Histories in the South Caucasus: Redrawing the Maps of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Iran, Bennett & Bloom, London, 2012.

- Historic Maps of Armenia, Abridged and updated, Bennett & Bloom, London, 2014.

- Armenia in the World Cartography, tri-lingual luxury volume, published by special order, 2015.

- Glance into the History of Armenia through Cartographic Records, Bennett & Bloom, London, 2015.

- History of the Armenian Cartography up to year 1918, Bennett & Bloom, London2017.

- Armenia, Azerbaijan and Turkey. Addressing Paradoxes of Culture, Geography and History. Bennett & Bloom, London 2019.

- The Borders of Armenia During 2600 Years of History, Zangak Publishing, Yerevan, 2022

- Articles and books are available for free download from author’s website www.roubengalichian.com

A Very Brief History of

Karabakh-Artsakh

Rouben Galichian

T

T

The publication of this book was made possible by a grant from the Tufenkian Foundation.

A VERY BREIF HISTORY OF KARABAKH-ARTSAKH / Rouben Galichian. Zangak, 2023. – 48 pages.

The booklet is targeting the general public interested in the history of Karabakh and especially students of senior schools and institutions of higher education, as well as foreigners who are interested in learning facts about the region.

Using simple and easily accessible language it explains the periodic changes in the borders of Armenia and Karabakh and the main reasons for these changes. This booklet presents especially a small collection of important maps made mainly by non-Armenians, part of which could be found in the author’s previous works. It also shows how the independent Republic of Artsakh was created and problems that is encountered henceforth.

The right of Rouben Galichian to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Acts.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher/author.

ISBN 978-9939-

© Rouben Galichian, 2023

Contents

TITLE PAGE

Author’s Note5

List of Images 7

A Very Brief History of Karabakh-Artsakh9

Glossary of Frequently Used Names43

Suggested Reading47

Author’s Note

I had prepared an article similar to this one about three years ago for Hrair Hawk Khacherian, to be included in his book of mainly photos about Karabakh. Text and images used in my other works have also been utilized here. After all, at the risk of being repetitive, if a map is needed, it has to be used irrespective of its previous usage.

Recently, after contact with many foreign officials, we realized that those who have come to assist us at this time of need have little background knowledge and information about the history and cultural background of the region. One Japanese tourist asked my friend, “how are you planning to kill all the Azerbaijanis”. This misinformation and impression that she had can only be attributed to Azerbaijani sources, whose textbooks prepare and inject the idea into the young generation, claiming that Armenians as killers, intent to kill all Azerbaijanis.

However, let us look at the facts as they really are. Yes, Azerbaijanis have a multitude of TV channels broadcasting their views and instigating hatred towards anything Armenian. Meanwhile the Armenian satellites air Armenian language TV serials for the Diaspora communities! How does that help our cause? It does not!

All incoming tourists to Azerbaijan are provided with packages of falsified information about their history and how the Armenians “newcomers to the region” have falsified Azerbaijani history and have claimed their culture. All of this is done without even mentioning that prior to 1918, there was no country named Azerbaijan located on the northern shores of the Arax River.

We lack government level proper planning for encouraging and promoting our historians and specialists to work on and research these subjects, as well as the wide and useful dissemination of the correct information about ourselves, our history, our political points of view, at the same time denying through European language TV satellite channels all sorts of Azerbaijani accusations and false news.

Few guests visiting our government and various ministries have much information about Armenian history and culture, and perhaps know less about Karabakh in general. Our authorities should make certain that all such visitors are provided with a basic package of information about history and culture of Armenia and Karabakh.

Specialists who have come to Armenia to help us have to obtain books and information from bookshops in order to learn a little more about Armenia, the Armenians, and our problems with our neighbours, and their reasons and justifications. All this is left to private specialists, who get hardly any assistance or guidance from the authorities and even if some little financial assistance is provided, the hassle and delays are not worth it.

Finally I would like to thanks the Research on Armenian Architecture (RAA) and Dr. Hamlet Petrosyan for supplying me with some of the images and data from Tigranakert, as well as Mr. Ashot Sargsyan, who provided me with some background historic data and my friend, Dr, Gagik Stepan-Sarkissian for editing the text.

Rouben Galichian

Yerevan, 2023

List of Maps and Images

Fig.

No. Description of the map or image

01 Map of the Ancient Armenia, Mesopotamia, Babylon & Assyria, by Karl von Spruner, 1865

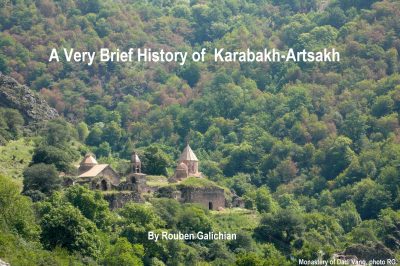

02 Dadi Vanq Monsatery in Kashatagh (Kalbajar) dating from the first to the seventeenth centuries

03 Tigranakert. General view of the Citadel

04 Tigranakert . Foundations of protective wall

05 Tigranakert. Typical construction in the Citadel

06 Tigranakert. The interlocking of Stone slabs.

07 Map of south Caucasus by Istakhri, around 950 CE

08 Detail form Persian language map made by Qarachedaghi in1869, Tehran

09 Detail from Fra Mauro’s’ World Map of 1460, Venice

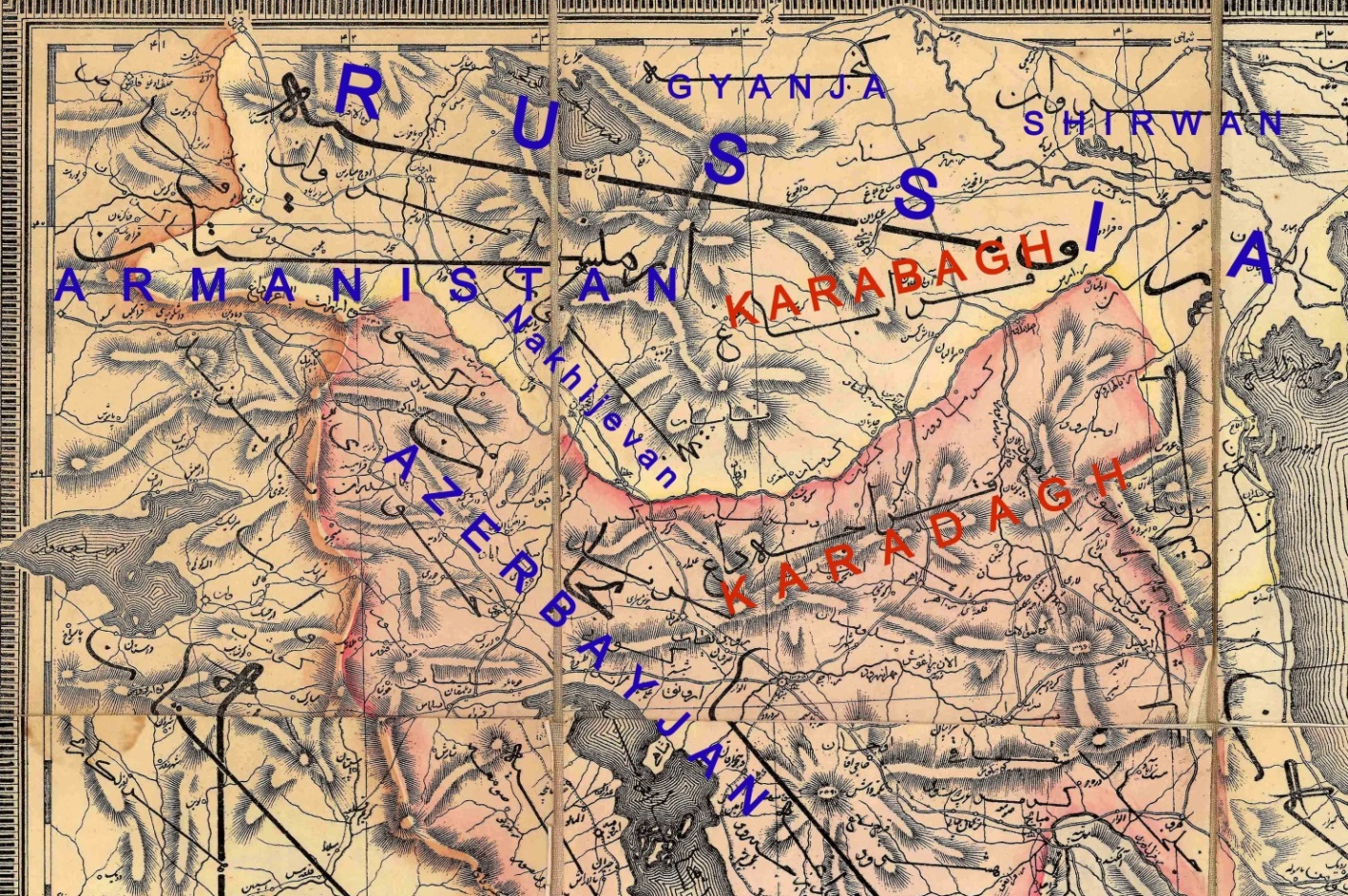

10 The regions ruled by Armenian Meliks during 17-19th centuries

11 Map of Armenia and Georgia by Robert Morden, 1680, London

12 Details form Lynch/Oswald map of Armenia and Adjacent Countries, 1901, London

13 Edward Weller’s Caucasus and Armenia, 1858, London

14 Heinrich Kiepert’s map of the region in 1916, Berlin

15 The Church of St John the Baptist in Gandzasar Monastery

16 The broken tombstone of St Gregoris

17 Replacement tombstone, after liberation, 2000

18 Monastery of Amaras

19 Armenian tombstone dated 1095

20 Armenian tombstone of 13th century

21 Two huge and intricately carved khachkars, Dadi Vanq, dated 1283

22 Armenian territory handed over to the Red Army in December 1920

23 Maps of Armenia, with regions (in blue) given away by Lenin and Stalin to Azerbaijan

24 Soviet Armenia according to the map taken from the Great Soviet Encyclopedia of 1926

25 Map of Armenia and Karabakh, with regions handed over to Azerbaijan marked blue

26 Map of the Karabakh region in March 2021

Inside Front cover – Miniature painting of the Last Supper, from Armenian manuscript of Karabakh. Matenadaran, Yerevan, MS-316, 13th century

Inside the back cover – Mural from Dadi Vanq Monastery, 1297.

Credits

02, 13, 16, 17, 18 –Inside back cover – Research on Armenian Architecture, RAA, Yerevan.

03, 04 – Dr. Hamlet Petrosyan, Yerevan.

National Library of Armenia

Matenadaran, Yerevan, R. Galichian Collection.

A Very Brief History of Karabakh-Artsakh

Historically Karabakh or Artsakh (in Armenian) refers to a region of the South Caucasus, which forms an almost equilateral triangle, whose tip is on the confluence of the Arax and Kura rivers, extending westward to the valley of Hagaru or Hagari river, which the Armenians call Aghavno, running on the eastern border of the Syuniq province of Armenia. The region has always been one of the provinces of Greater Armenia, recorded since before the Common Era.

Genetic research, published in the world-renowned journal Current Biology, published by Cell Press in the United States, (a subsidiary of the Dutch group Elsevier), in its 2017 issue, pp. 2023-2028 reports that Armenians living in the regions of Artsakh and Syuniq have continuously lived in the same region for at least eight to ten thousand years.

In the early centuries of the Common Era, Greater Armenia extended eastward up to the river Kura, and included the Armenian provinces of Utiq, Artsakh and Syuniq, all located in the region between the Kura and Arax rivers. The Greek geographerm philosopher and historian Strabo (63BCE-24 CE)names the region to the north of the eastern end of the Kura River as Caucasian Albania, which the Armenians call Aghvanq and the Persians and Arabs call Ar(r)an.

According to Strabo, in the region of Albania there lived 26 tribes (Strabo – Geography, 11.4.6 . Harvard, 2000), who did not understand each-other’s language. Even today, after 2000 years, the population of that region, which is presently the greater part of the Republic of Azerbaijan consists of Lezgins, Avars, Talishes, Tsakhurs, Ingiloys, Udis, Turks, Kurds, Tatars and others, who have been made to forego their mother tongues and have been compelled to use the local; Turkish language, imposed on them by the invading Central Asian Turkic and Seljuk tribes, who ruled the region during the 13-15th centuries.

Fig. 01 – Map of the Ancient Armenia, Mesopotamia, Babylon & Assyria, by Karl von Spruner, 1865.

Eastern provinces of Greater Armenia are underlined in red and Albania – blue.

According to Strabo, at the same time the Greater Armenia, mentioned above, included – the provinces of Artsakh and Utiq, (later known as Karabakh), as well as Syuniq, which were mainly populated by Armenians. These are shown underlined in red, Figure 01. The blue line underlines name of Caucasian Albania, located north of the Kura River, which in Persian and Arabic is Arran and in Armenian – Aghvanq.

Today the language spoken in Azerbaijan is wrongly called Azeri, which was the local language of the people of the Iranian province of Azerbaijan until the 15-16th centuries. Afterwards the language of the Turkic overlords was gradually adopted by the locals, since their language did not have a written form, it gradually almost disappeared. Thus, language of the conquerors gradually replaced the language of the locals, while the Armenian population of the region, living under the same rule and conditions, managed to save their language, because it was a written one (Kasravi – Tehran, 1973). The example of this language replacement could be seen in Brazil, whose official language has now became Portuguese, as well as in Mexico and Philippines whose population lost their languages and now speak Spanish.

Fig. 02 – The oldest Christian monument in Karabakh is Dadi Vanq Monastery in Kashatagh (Kalbajar)dating from the first to the 17th centuries. It was partially restored by Armenians in the early 2000s.

See also Fig. 21.

One of the oldest Armenian monuments found in Karabakh is the fort city of Tigranakert, perched on the easternmost hills of Mountainous Karabagh (Nagorno-Karabakh), approaching the Karabakh Steppe, seen on Fig. 10. During 95-55 BCE the Armenian king Tigran the Great ruled overran extensive empire stretching from the Caspian Sea to Lebanon. According to some written records he had built other forts bearing the same name, but this one is the only excavated and proven site bearing his name.

After liberating most of Karabakh, in 2005 a group of Armenian archaeologists noting the telltale line of stones began their search and undertook excavations in 2006, discovering r large towers and ramparts of the town and the citadel dating back over 2000 years. After the 2020 war, Azerbaijan has occupied that site.

The city occupied an area of around 70 hectares and was built as per the Hellenistic construction principles, with terraced housing regions, cemetery and cultivating lands, which were in use until the thirteenth century.

This is one of the best preserved Hellenistic architectural examples.

Further excavations revealed the evidence about the detailed care take in the construction of wall and towers, which proves this to be an important site.

Fig. 03 – View from the Citadel

Fig 04 – Foundations of protective wall.

Fig.05 – Typical construction in the Citadel

At the lower slopes of the hill the foundations of two Christian churches and other religious monuments have also been excavated, many bearing Armenian inscriptions, now in danger of being destroyed by Azerbaijanis..

Fig 06 – The dovetailed interlocking system for the stone slabs

In Islamic cartography, which reached its apex during the tenth to thirteenth centuries special maps were dedicated to the south Caucasus.

On these maps one can see three countries, which are listed in the texts with the names of their cities and lakes etc. These include Azerbaijan, as a province of Iran located south of the river Arax. The other country is Arran (Caucasian Albania) which is shown as a separate country to the north of the Arax and Kura rivers and includes the cities of Karabakh. The third country shown is Armenia, which is placed straddling the river Arax and extending westward.

Thus, in spite of President Aliyev’s claim that in fact Albanians are ancestors Azerbaijanis, Islamic maps prove that Albania and Azerbaijan were two distinctly separate countries.

Fig. 07 – Map of the South Caucasus by Istakhri, around 950 CE. The Caspian See is at the right, Lake Van is at the near the bottom of the map. The twin Ararat mountains are below left and Mount Sabalan of Iranian Azerbaijan in the middle of the map. The rivers in the north are Arax and Kura.

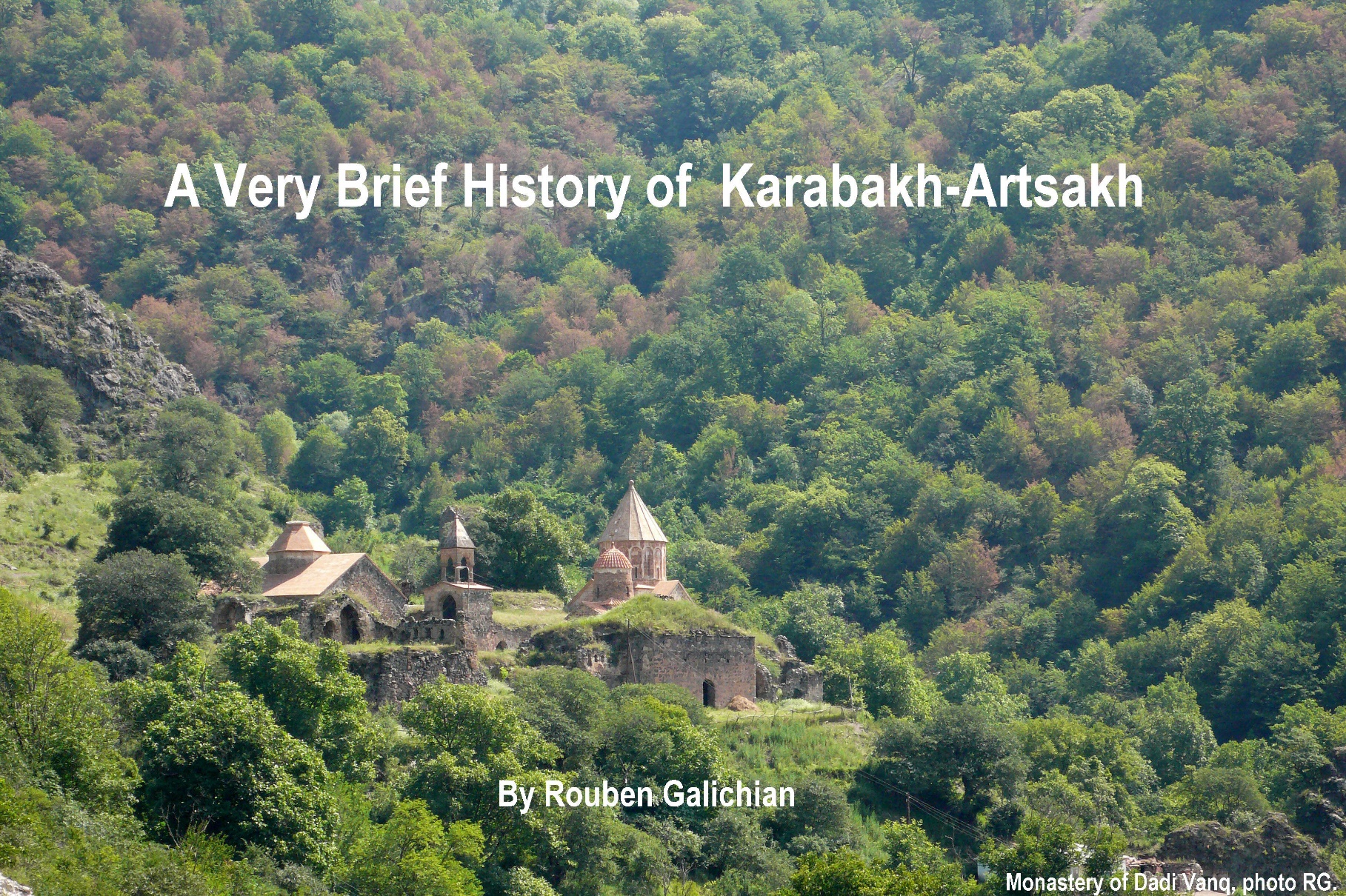

Fig. 08 – Detail form a Persian language map made by Qarachedaghi,Tehran,1869, showing the border between Iran and Russia. Armenia is shown inside the Russian Empire, together with Karabakh, while the region today occupied by Azerbaijan is named Shirvan. Azerbaijan is shown as a province of Iran, placed on the southern shores of the Arax.

Fig. 09– Detail from Fra Mauro’s’. World Map of 1460 è

This is the central part of the map of the Venetian monk Fra Mauro, made in 1460 Venice. On the map, the south is located at the top.

Here one can see the Caucasus and its western and southern regions. In the western vicinity of the Caspian and east of the Black seas, as well as in the corner of the Mediterranean (top right), the name “Armenia” is shown five times. First as the “Greater Armenia”, then (in 3 places) as just “Armenia”, and finally at the top of the map near the corner of the Mediterranean the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia is indicated, named “Armenia”. On the map all the toponyms of Armenia are underlined in red.

In the central region of Armenia, the mapmaker has drawn a mountain, near which we see the name “Ararat”. On the top of the mountain there is small house like structure which is denoted as “Noah’s Ark”. Both the toponyms of Ararat and Noah’s Ark are underlined in blue.

To the left of Ararat and Noah’s Ark, which is to the east of them there, we see a group of mountains bearing the description “Montes Charabach”, (Mountains of Karabakh), underlined in green. On this map of 1460. For the first time in Western cartography the name of Karabakh could be seen on this map.

Mentioning the name of Armenia several times is an indication that amongst the educated and commercial society of Europe Armenia was a recognized and important country. Amongst Armenia’s neighbouring countries only the names of “Georgia” and “Abkhazia” are shown once, placed near the Black Sea, while near the Caspian Sea, east of the names of Armenia there is only one name, “Shirvan”. The name Azerbaijan is totally missing from Fra Mauro’s World Map.

The Armenians living in the same region adopted Christianity in the fourth century CE. Some decades later, in 314 CE the Albanian tribes living in the neigbourhood also adopted Christianity, but after the invasion of the Arabs during the period between the eighth to thirteenth centuries, most Albanian tribes converted to Islam, with the exception of Udis and Tsakhurs, who today number only a few thousand (Galichian – 2012).

Recently President Aliyev, while visiting his occupied Armenian villages announced: “all the churches in the region are actually Albanian, and the Armenians have appropriated them”; oblivious to the fact that those monuments were mostly built between the twelfth to nineteenth centuries, when the majority of the said tribes had already converted to Islam. A few thousand Christian Udis could never have built so many monasteries, churches and chapels, which still abound in the region.

However, the recently published evidence (BBC TV “Why did this Church Disappear” March 25, 2021) show that these monuments are only awaiting destruction in the hands of the henchmen of President Aliyev.

During the Middle Ages Artsakh was ruled by various kings and emirs installed by the ruling Ottomans or Persian, who paid tribute to their sovereigns. Notwithstanding this, the Armenian landowners, called Meliks of Mountainous Karabakh; because of the region’s mountainous terrain were able to defend their territories and keep their autonomy, surviving and being granted relative independence by paying taxes to the ruling emirs or khans of Iran or the Ottomans, whoever ruled the region.

Fig. 10 – Regions ruled by Armenian Princes, named “Melik”s during 17-19th centuries, indicated orange with the names in blue.

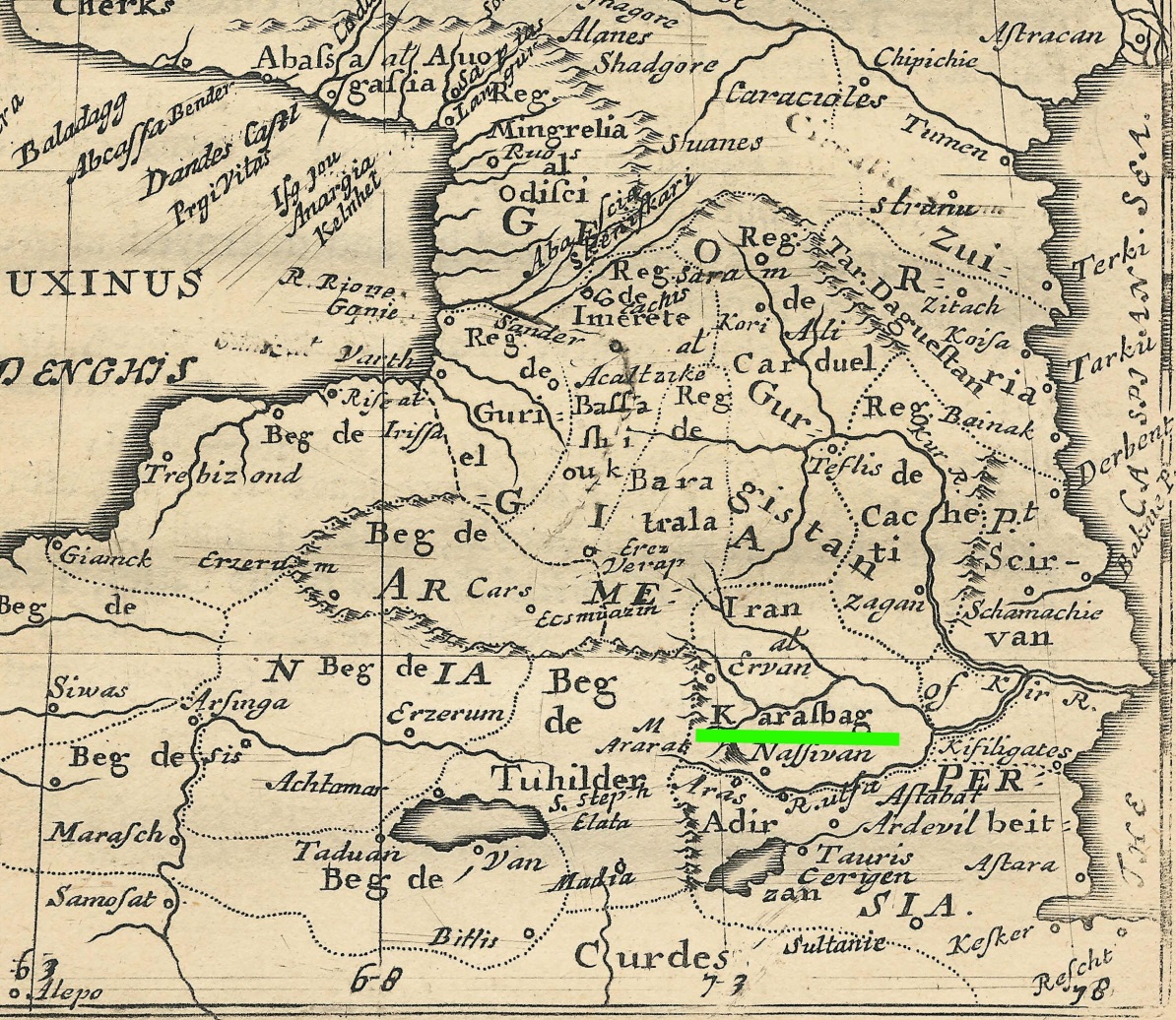

On maps of the following pages regarding the region, all prepared by various European mapmakers of the Middle Ages and later, the region of Karabakh can be seen, distinctly located near the confluence of the Kura and Arax Rivers.

Map of Figure 11 is by a British cartographer, who has shown the region of Karasbag(kh) inside the territory of Armenia, located near Lake Van and Nassivan (Nakhijevan), extending to the confluence of the Aras (Arax) and Kir (Kura) Rivers. The name Karabakh is underlined in green.

Fig- 11. “Map of Armenia and Georgia” by Robert Morden, 1680, London

Henry Finnis Blosse Lynch, was a well-known Irish-British traveler and geographer who, during the last years of the 19th century together with his colleague F. Oswald visited Turkish and Russian held territories of Armenia and published a two volume book “Armenia: Travels and Studies. Volume I: The Russian Provinces” and “Armenia: Travels and Studies. Volume II: The Turkish Provinces. The books contain detailed information about the people and their life and culture.

The volumes were accompanied by a large and detailed insert stand-alone map of the region, prepared jointly by Lynch and F. Oswald, dated 1901. Lynch was very interested in Armenia and twice travelled to the area, first in 1893, and then in 1898. His volumes contain many sketches, maps and unique photographs of the country and its peoples, which today remain important historical documents for the people as well as old churches and monuments hence destroyed or fallen down.

The map shows all the geographical features and contains a large amount of detail, such as the names of villages, rivers, mountains and their heights, and the borders of vilayet and countries. It is noteworthy that at the time, the territory of Russian (Eastern) Armenia included Kars, Ardahan, Childir, Igdir, Bayazid and Mount Ararat. All these regions were handed over to the Ottoman forces, decreed by the Red Army, in order to please the Ottoman authorities and draw them towards their communist camp.

The name of mountainous region of Karabakh appears on the map extending form the south east of Lake Sevan to the region of the Persian border near Horadiz. A second time the name appears relating to the lowlands of Karabakh, here named “Karabagh Steppe” on an area extending eastwards from Martakert to the confluence of Kura and Arax rivers.

On the map both of Karabakh regions are underlined in red.

Fig. 12 – Details form Lynch/Oswald map of Armenia and Adjacent Countries, 1901, London è

Fig. 13 – Edward Weller’s “Caucasus and Armenia”, 1858, London

Karabakh is the region from Sevan to the confluence of the Kura and Arax Rivers, underlined in red. The region of present-day Azerbaijan is shown as Sheki and Shirvan. There is no Azerbaijan on the map, except the Persian province bearing that name.

Fig. 14 – Heinrich Kiepert’s map of the region in 1916, Berlin. Here Karabakh is placed between Syuniq and the confluence of the Kura and Arax rivers, while the region of present-day Azerbaijan is shown as Sheki and Shirvan.

Fig. 15 – The Church of St John the Baptist in Gandzasar Monastery è

One of the pearls of medieval Armenian architecture, the Monastery of Gandzasar has always attracted the attention of specialists in different branches of art, architecture and history.

The construction of the church lasted for 22 years (1216 to 1238) and it was eventually consecrated in a solemn ceremony in 1240. The Armenian historian Kirakos Gandzaketsy (13th century) reports important information relating to the erection of the sanctuary. According to Prince of Khachen, Hasan Jalal-Dowla, the church was built in the monastery called Gandzasar, opposite Khokhanaberd. Once it was completed a solemn preliminary ceremony was held to consecrate it. Present were the Catholicos of Aghvanq, lord Nerses with many bishops… the holy vardapets of Khach’en, Grigoris and lord Eghia, these dignitaries altogether numbered some seven hundred.

This occurred, on the day of the great Feast of the Transfiguration in 1240. Later a vestibule was built under the patronage of Prince Hasan Jalal-Dowla’s wife Mamkan, leading to the nave of the church.

In 1261 Great Prince of Khachen Hasan Jalal suffered martyrdom in the hands of Arghun Khan, and his remains were buried next to his forefathers’ graves in the Monastery of Gandzasar.

In 1607 the Persian king Shah Abbas, who had ruled the area, issued a decree exempting Gandzasar Monastery from a tax called tafaut-e jizia.

The name of the monastery is also found in a decree (1650) issued by Shah Abbas II in which the monarch banned the Catholicosate of Aghvanq in Gandzasar from intervening in the affairs of Shamakhi Diocese, which was to be within the jurisdiction of the Armenian Catholicos in Echmiadzin. The two Catholici were often in competition for expanding their influence in the neighbouring communities of the faithful.

During 1994 and 2020 war, Gandzasar became a center for learning and research with a library containing many manuscripts and religious text. During those years it also attracted many tourists and visitors from all over the world.

Fig. 16 – The broken tombstone of St Grigoris Fig. 17 – Replacement tombstone, after liberation, 2000

Fig 18–Monastery of Amarasè

The celebrated monastery of Amaras was founded by Gregory the Enlightener in the early 4th century. It became particularly well-known in the mid-4th century, when Gregory the Enlightener’s grandson, Catholicos of Caucasian Albania, St. Grigoris was buried there (he had suffered martyrdom for his efforts in disseminating Christianity).

In the late fifth century, the king of Caucasian Albania Vachagan the Pious had a dream which helped him find Grigoris’s remains: the king ordered that the bishops should distribute the relics among their dioceses, leaving most of them in Amaras. He also ordered that a chapel should be founded over the grave as soon as possible, to be dedicated to St. Grigoris. During the fifth century, Amaras was serving as a bishop’s residence.

In 821 the monastery was invaded by Arabs from Bardaa (Partaw), whose forces left their base secretly and attacked the district of Amaras, taking one thousand captives.

During the 1992-94 war, the Azerbaijanis broke the tombstone of the Albanian Catholicos Grigoris in Amaras. When Armenian forces liberated the monastery, they replaced it with a newly carved one, (Figures 16 and 17.)

The question has not been asked; if the Azerbaijanis claim that the Albanians were their ancestors, then why do they destroy the tombs of their own ancestors?

Fig 19 – Armenian tombstone dated 1095

Fig. 20 – Armenian tombstone dated 13th century

The Monaastery of Dad (Dadi Vanq) is the oldest Chrisitan monument in Karabkh, dating form the 1st to 17th centuries CE, located near the village of Vanq. Tradition says that the original structure of the monastery, presently known as Dadi Vanq had been constructed on the tomb of St. Dad, who was one of the pioneers preaching Christianity in the South Caucasus, and was martyred for his belief, being buried in the village of Vanq.

Reports are extant stating that during the fifth century CE, this was an episcopal centre. During the earlier part of the twelfth century it was destroyed by the invading Seljuks. However, the importance of the site was such that during the period of twelfth and thirteenth centuries a new monastery was constructed on the site, complete with two large and a smaller religious, as well as a multitude of secular buildings. See cover picture as well as Fig. 02.

Fig. 21 – Two huge and intricately carved khachkars, dated 1283, symbolising the monastery. Both khachkars stood under the bell tower in a specially built alcove

inside the Monastgery of Dadi Vanq. They measeure 273 and 297 cm high and about 98 cm wide.

The Persian occupation of South Caucasus lasted from the seventeenth century until 1828, when the Czarist Russia finally succeeded to execute its long-planned occupation of the South Caucasus, which they had named Transcaucasia. Russia immediately began carving the region into various administrative Provinces or Gubernias, in order to suit ease of their administration, paying little attention to the ethnicity or the religion of the indigenous populations of each region. The layout of this administrative provinces were regularly undergoing major changes, executed as per the whim of the Russian rulers of Transcaucasia.

In 1823 the Tsarist regime, who had their Viceroy installed in Tbilisi, ordered Colonel Ermolov to prepare a census of the region of Karabakh. The resultant tables were only published in Tbilisi in 1866, entitled “The Description of Karabakh Province”. The volume consist of tables of population of each town and village, including the names of the families and the family head counts, plus amount of annual tax paid by each family. The published tables show that in the province of Karabakh over 90% of the sedentary population was Armenian and the rest were mainly nomadic tribes, who did not have a fixed abode. (Polkovnik Ermolov – Opisanie Karabagskogo Provincii v 1823 god, Tbilisi, 1866) .

In 1918, after the end of World War I and the withdrawal of Russia from the war, three countries in the South Caucasus announced their independence. Georgia and Armenia reverted to their old names, while the newly established Muslim republic, had planned to be named Southeastern Caucasian Muslim Republic. However, after consultation with the Ottomans, the local extreme nationalist leader Mohamed Emin Rasulzadah, it was decided to call the newly born country Azerbaijan, borrowing the name from the neighbouring Iranian province, situated south of the River Arax, which was known with that name from the time of the invasion of Alexander the Great.

This intentional misnomer was planned by the local politicians so that in future they could claim ownership of the Persian province as well, which they tried to do in 1947, which was also announced after independence, by the Azerbaijani President Elchibey, in 1992. The present regime of the Republic of Azerbaijan intermittently announces such plans and decisions, by naming themselves Northern Azerbaijan and naming the Iranian provinces as Southern Azerbaijan, claiming that Russia and Iran have split the country into two parts and soon they will reunite the two halves. Notwithstanding the fact, that north of the Arax River a country named Azerbaijan never existed until 1918. Thus the country born in 1918 lays claim to a 2000-year old neighbouring regions and provinces.

Fig. 22 – The territory of Armenia handed over to the Red Army in December 1920

In 1918 both Azerbaijan and Armenia claimed ownership of Karabakh, which had 92% Armenian population and included the regions of Kalbajar, Lachin and Syuniq. While General Andranik was preparing to liberate Shushi, a city of 42,000, which included 23000 Armenians, the British General Thomson, resident in Baku, suggested him to stop the attack and promised that Shushi will be given to Armenia peacefully. Andranik withdrew and later Shushi was not given to Armenia, but to Azerbaijan (Walker – p.394). Meanwhile Azerbaijan did not lose time and in March 1920, in order to make Shushi a Muslim city, massacred the majority of city’s Armenian population, while the remnants escaped to other regions.

Communists overran Azerbaijan in April and Armenia on 29 November 1920. On November 30 the Azerbaijan government issued the following declaration that the disputed regions of Nakhijevan and Karabakh, which were subject to disputes, should be under Armenian rule. This ruling was published in Moscow, Baku and Yerevan.

The Worker’s government of Azerbaijan greets the victory of the rebellious peasantry of brotherly Armenian nation and the establishment of Soviet Socialist rule. As of today the border disputes between Armenia and Azerbaijan are declared resolved. Mountainous Karabagh, Zangezur and Nakhijevan are considered part of the Soviet Republic of Armenia.

Signed by the President of Revolutionary Committee of Azerbaijan N. Narimanov, and

Peoples’ Commissar of Foreign Affairs Huseynov. (Pravda newspaper, #273, dated 4.12.1920)

Immediately thereafter Moscow handed over the region of Kars to Ottoman Turkey. In June 1921 Lenin gave 50% Armenian populated Nakhijevan the title of “Autonomous Territory” and handed it over to Azerbaijan, notwithstanding that they lacked a common border and were separated from each other by the Armenian province of Syuniq. When Stalin visited Baku on the 4h of July 1921, he confirmed this ruling about Karabakh to be Armenian, but after a secret meeting with the head of the Azerbaijani government, Mr. Narimanov, the next day the Caucasian Bureau announced that Karabakh will also be handed over to Azerbaijan, as an autonomous region. Thus placing 95% Armenian populated Karabakh, as well as Kelbajar, Lachin and eastern Syuniq under Azerbaijan’s control. Today we are suffering the results of these irrational decisions of the Soviet leadership. On Fig. 21, these lost areas are circled by green line.

Fig. 23 – Maps of Armenia, with regions given away by Lenin and Stalin to Azerbaijan, circled green

Fig.24– “Soviet Armenia” according to the map published by the Great Soviet Encyclopaedia of 1926. è

This map of 1926 shows the territory of Soviet Socialist Republic of Armenia as it stood on the 1st of April, 1926. The regions marked green on this map are the ones handed over to Azerbaijan during the following decades and under various unjustified pretexts.

The remark “Borders of Armenia on April 1,1926″ is printed at the bottom of the map”. In the Soviet Union if a map was printed, then it must have had the approval of several ministries. This map also bears the names of the approving authority, which is the Ministry of Security. Therefore, as far as practically possible, the map shows Armenia’s true and actual borders during 1926. It is noteworthy that on this official map of the Soviet republics, including that of Azerbaijan from the same encyclopedia, there are no enclaves either in Armenian or in Azerbaijani and territories and the region of Artsvashen, which later became an Armenian exclave in Azerbaijan, was completely inside the borders of Armenia.

When, in October of 2021 President Putin announced that Russia must also participate in the new delimitation and demarcation process to take place between Armenia and Azerbaijan, he reasoned that, only Moscow has the required accurate maps for this purpose. As far as official maps go, all interested parties have copies of the Soviet General Staff maps made between 1929 and 1980s, however earlier maps, such as the above-mentioned 1921–1923 detailed topographic maps, are held solely by Moscow and so far no copy has ever been given to the interested parties. Hence, it could be concluded that maps mentioned by President Putin are the maps of General Staff prepared during the early 1920s, which would be the main source of the map of Fig. 24 on the opposite page, not favouring Azerbaijan!

It must be mentioned that on this map Armenia and Artsakh have a common border and they are only separated by the Hagari or Aghavno River, marked blue on the map. The border, however, was changed at a later date, with Azerbaijan appropriating further territories from Artsakh, in order to cut thjis Armenian populated region off from Armenia.

During 1923 the Azerbaijanis announced their decision to establish a new province of Red Kurdistan, as a buffer zone between Karabakh and Armenia. To this end, during the 1923-1929 they appropriated pastures from Armenia and took some from Karabakh as well, which were to be earmarked to be pastures for Red Kurdistan. However, in 1932 this decision was revoked and Red Kurdistan was not created, but all the territories which were to be allocated to Red Kurdistan were appropriated by Azerbaijan. Thus Armenia and Karabakh lost almost 1500 square kilometers of land to Azerbaijan, and Karabakh was separated from Armenia by the Azeri occupied region of Lachin, thus the two Armenian populated regions were cut off from each other.

From 1921 to 1990 inside Azerbaijan, the Armenian populated Karabakh was repressed by the central Azeri government through closing of the Armenian University, Armenian radio programmes and delaying, even preventing any economic growth. This and other manners of ethnic cleansing practiced in order to reduce the Armenian population of Karabakh and Nakhijevan. It must be said that they were partially successful. By the late 80s the whole Armenian population of Nakhijevan was driven away and today there are no Armenians living in Nakhijevan, neither are there any traces of the multitude of Armenian monuments and monasteries which existed there for many centuries up to the late 1980s.

The promises made by “Glasnost” about the establishment of democracy and the restoration of historical justice in the Soviet Union also inspired the population of Nagorno-Karabakh. Here, the issue was aggravated due to the national and social pressures from Azerbaijan, which threatened the deportation of the whole Armenian population living in Azerbaijan, numbering over 300,000.

On 20 February 1988, the highest authority of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region olrganised a referendum and adopted the decision to withdraw from Azerbaijan and join the Soviet Republic of Armenia, addressing this to the authorities of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Moscow.. The issue was not unusual; such changes of administrative borders had been made dozens of times in the USSR (for example, Crimea was given to Ukraine).

In support of the demands of the people of Karabakh, a massive national movement began in Armenia; the number of rally participants reached half a million after just one week. Soon the movement turned into a broad-based democratic struggle against the Soviet system.

Fig. 25 – The map of Armenia and Karabakh, with regions handed over to Azerbaijan marked in blue.è

During the Soviet days, the people of Karabakh had organized and prepared numerous petitions for independence from Azerbaijan, which were sent to the USSR central government, but all were completely ignored. In 1988 the people of Karabakh, announced their will to join Armenia.

Before the start of the hostilities in earnest, in May 1991 the Soviet troops, while assisting Azerbaijan , forcibly evacuated the population of northern Artsakh Armenian village of Getashen, whose 3600 souls were forced out of their ancestral homes and driven to other regions, thus perpetrating an ethnic cleansing operation for their friend, and ally – Azerbaijan. The same possibly awaits the whole of the 120,000 population of Karabakh, if and when it is handed over to Azerbaijan.

The Armenian democratic movement had an impact on the emergence of similar movements in the USSR and Eastern Europe, which in 1991 ultimately led to the collapse of the USSR. It became clear that the Nagorno-Karabakh problem could not be solved under the leadership of the USSR. Therefore, on December 10 of 1991, before the collapse of the USSR, , a referendum was held in Nagorno-Karabakh in accordance with the relevant laws of the USSR, as a result of which the region was resolved for Artsakh to become free from Azerbaijani rule.

This decision instigated Azerbaijani pogroms in Baku and Sumgait, an industrial city near Baku, and as a result scores of Armenian were killed and over 400,000 Armenians resident in Azerbaijan were forcefully expelled from Azerbaijan, leaving everything behind.

After the collapse of the USSR, the Nagorno-Karabakh issue acquired the status of an international importance. As punishment for daring to seek independence, in the early 1992 Azerbaijan launched a full-scale war against Nagorno-Karabakh. Armenia had to assume the role of guarantor in the economic and diplomatic spheres for the population of Karabakh, who were facing the real threat of deportation and even genocide. Initially only volunteers from Armenia participated in the self-defense operations in Karabakh.

Towards the end of the war the armed forces of Karabakh occupied some Azerbaijani border regions, in order to create a security buffer zone for their territory. The resolutions adopted by the United Nations on the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh also state that these regions were occupied by the armed forces of Nagorno-Karabakh.

In spite of all the problems and lack of ammunition etc., in 1994 after about four years of conflict the Armenians won the war. In May 1994 a ceasefire was negotiated, under which the relevant officials of Azerbaijan, Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh signed as equal parties. In the same year the OSCE summit recognized Nagorno-Karabakh as an equal party to the conflict with Azerbaijan. Accordingly, during 1997-98 the Minsk Group sent the settlement documents to Azerbaijan, Yerevan and Nagorno-Karabakh, with each party having the right of veto?

Since 1980s Azerbaijan’s authorities had begun the use of the term “Western Azerbaijan”, which they apply to the territory of the Republic of Armenia, naming the land as the birthplace of their ancestors, the Oghuz Turks, who, in fact, were nomadic tribes living in the region to the east of the Caspian Sea. To overcome this obstacle Azerbaijani academicians and historians claim that the Oghuz Turks originate from the South Caucasus, and have published a book entitle “The Monuments of Western Azerbaijan”, (Alekbarly – Baku, 2007) where the map of Armenia is called Western Azerbaijan, the home of Oghuz Turks, where all pre-Christian and Christian monuments in Armenia are claimed to be Turkic and Christian-Turkic monuments, whoever these Christian Turks were?.

For the next 26 years the Russian arranged ceasefire was intermittently broken by Azerbaijan and every few years skirmishes flared up in a various corners, until on September 27, 2020 Azerbaijani army, led by the Turkish military experts, special forces, thousands of Arab and other mercenaries and weaponry supplied to Turkey and NATO, including NATO fighter jets and thousands of drones, attacked Karabakh as well as Armenia. Azerbaijan used internationally banned cluster bombs and phosphorus incendiaries and poisoned bullets in their arsenal, in order to cause maximum injury to civilian as well as military targets.

In 44 days of fighting these huge forces retook the entire buffer zone as well as parts of Karabakh, culminating in the occupation of some 30 percent of the Karabakh territory as well as the return of their regions lost in 1994.

On the ninth of November 2020, Russia, by-passing the Minsk Group, forced a ceasefire agreement between Armenia and Azerbaijan, whereby all forces would return to their 1991 country borders, prisoners of war would be exchanged, Russian peacekeepers would take up the responsibility of the security of the people of Karabakh as well as securing their access to Armenia through the Lachin or its alternative corridor.

It is imperative to state that the Russian peacekeepers have not been performing their undertaking, the protection of the local population in Karabakh, and on many instances the Azeri forces have advanced into the territory of Karabakh with impunity.

Notwithstanding the ceasefire of 2020, in May 2021 the Azeri forces began the process of occupying various heights and regions of Armenian sovereign territory as well, and in spite of agreeing that peace negotiations should begin as soon as possible, Azeris are showing no signs of leaving their occupied Armenian and Karabagh lands.

In September 2022 Azeri forces once again attacked Armenia, trying to create a corridor through the northern Syuniq region, in order to connect Azerbaijan with Nakhijevan, via a corridor through Armenian lands, thus cutting Armenia into two halves. The attempt was unsuccessful, but some 200 Armenian soldiers were lost and Azerbaijan occupied about 140 sq. km. of Armenian sovereign territory.

Armenia has announced that it will do everything in its power to open rail and road communication for Azeris though Armenian sovereign roads, but Azerbaijan wants to have the ownership of the corridor and to this end has unilaterally inserted a new term in the Nov. 9, 2020 Agreement about having been promised a corridor of Azeri land, connecting Azerbaijan with Nakhijevan, thus arranging to split Armenia in half, blocking its access to Iran and further south.

The relentless insistence of Azerbaijan to secure a “corridor” though Armenia connecting Azerbaijan with Nakhijevan, which they claim should be controlled and run by Azerbaijan, leads us to believe that this is not just a plain land route for Azerbaijan, but in fact it is to complete the direct link of the Pan-Turkic belt of countries with each other, which Armenia blocks, having its historic presence on this path as a wedge.

The Pan-Turkic belt was planned as a continuous belt of Turkic speaking countries, extending from the Balkans to eastern Siberia.

This belt, originally was planned in the middle of the nineteenth century and was further revived by the Grey Wolves extremist organization, as recently as 1960s. In 2021 its proposed map was demonstrated by the leader of the Grey Wolves movement of Turkey showing their planned belt, the print of which was gifted to President Erdogan. It is apparent that in the first instant the construction of this long planned belt had the primary aim of blocking the access of Russia to the warm waters of the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean in the south, thus curtailing their influence and interests reaching south, towards the Muslim world at large.

The end result of these political misinterpretations and disputes have resulted in Azerbaijan actually blocking the road between Karabakh and Armenia in December 2022, which the Russian peacekeepers had the responsibility to control and keep open. The blockade was declared illegal by the International Court of the Human Rights, but Azeri authorities has paid no attention to the court’s decision, or to all the criticism and suggestions for removing the blockade have, so far, been completely ignored.

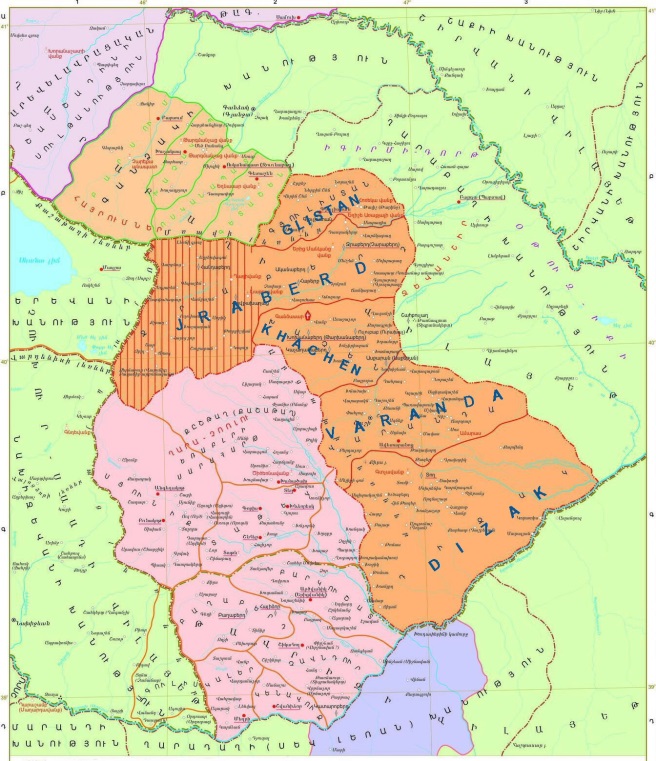

Fig. 26 – Map of the Karabakh region in March 2021.

Before Azerbaijan began its further incursions into the Armenian sovereign territories.

1 – Pink . Armenia

2 and 3 – Light green. Azerbaijan & Nakhijevan

4 – Dark green. Kalbajar,

5 – Dark green. Lachin,

6 – Dark green. Aghdam (from 1994 this regions was a buffer zone in Armenian hands). All the areas indicated by 4, 5, and 6 were handed over to Azerbaijan on 9-11-2020, as per the tripartite declaration.

7 – Blue. Regions of Azerbaijan, which Armenia had occupied as buffer zones.

The Azerbaijani, Turkish and mercenary forces, with the help of the NATO air force overran this region.

8 – Blue. Part of Nagorno Karabakh republic, occupied by the above mentioned forces.

9 – Orange. Remaining part of Karabakh, where the Russian peacekeepers are supposed to protect from Azeri aggressions and incursions.

© Rouben Galichian

May, 2023. Yerevan

Glossary of Frequently Used Names

Aderbigan or Adherbizan – see Azerbaijan.

Albania or Caucasian Albania – Historic country located south of the Caucasus Mountains and north of the Kura River, where most of the present-day Republic of Azerbaijan is situated.

Anatolia – The old name given to Asia Minor. In Greek this means ‘Where the sun rises from’, i.e. to east of Constantinople.

Ararat – Holy Mountain of the Armenians, located in Armenia, now located in the Turkish border. This is where according to the Bible Noah’s Ark landed. Armenians call it Masis. It has two peaks: Greater Ararat or Greater Masis with a height of 5165m, and Lesser Ararat or Small Masis with a height of 3903m.

Arax or Araxes, Araz – River on the borders of Turkey, Iran and Armenia, flowing to the Caspian Sea. For the Armenians this river has been historically important.

Armenia – Country to the east of Anatolia and south of the Caucasus range, situated on the Armenian Highlands and the areas nearby. Armenia is divided into two parts: Greater Armenia (Armenia Maior) and Lesser Armenia (Armenia Minor). Greater Armenia is the part that is situated in the Armenian Highlands, as well as the area to its northeast (present day Republic of Armenia). Lesser Armenia is located on the western side of the Highlands, in the eastern part of Anatolia. Armenia has also been called the ‘Land of Ararat’.

Armenian Highland(s) or Plateau – A mountainous plateau, situated in Eastern Turkey and the Republic of Armenia, extending into the northwest corner of Iran. The mean elevation of the plateau from the sea level varies between 1000 and 2000 metres, the area covered is over 300,000 sq. km.

Ar[r]an or Caucasian Albania – Historical names given to the approximate area of the present-day Republic of Azerbaijan.

Artsakh or Nagorno-Karabakh – Armenian populated region, presently located in Azerbaijan as an autonomous region, as per the 1921 decision of the Caucasian Bureau. The region consists of the Utiq and Artsakh provinces of historic Armenia.

Asia Minor – Name of the peninsula between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. The Byzantians called it Anatolia. (See Albania.)

Atropatene or Atropatena – Old name of the Iranian Province of Azerbaijan, previously ‘Lesser Media’.

Azerbaijan – There are two regions named Azerbaijan. One is the historic Persian (Iranian) province of Azerbaijan, located south of the Arax River (now regrouped into three provinces of Eastern, Western Azerbaijan and Ardabil province). Persian Azerbaijan has existed for centuries as Lesser Media, later renamed Atropatene, Aderbigan, etc., named after the ruler of this land, Atropat, during 321 BCE. The other is the Republic of Azerbaijan, born in 1918 and situated north of the Arax River, west of the Caspian Sea, southeast of the Caucasus and neighbouring Armenia, which until around the tenth century was known as Caucasian Albania (Arran, in Arabic and Persian) and later, until 1918, was principally known as Shirvan.

Black Sea – It is also known as Pontos Euxinos or Pontus. This is the sea located north of Anatolia.

Byzantium – The Eastern Roman Empire that ruled over Anatolian part of present-day Turkey and surrounding regions, with its capital in Constantinople, by the Sea of Marmara.

Caspian Sea – The largest of the inland lakes, situated to the north of Iran, south of Russia, between the Caucasus and Central Asian republics. It is also called the Hi(y)rcanean Sea, Bahr-e-Khazar (in Arabic), the Sea of Tabarestan or Sea of Gilan.

Catholicos – The highest religious leader of the Armenian Apostolic church, who ruled over the religious life of a designated part of Armenia, named their “sea”.

Cilicia or Armenian Kingdom in Cilicia– Area in the north-eastern corner of the Mediterranean Sea, inside Anatolia and near the Gulf of Alexandrette (Iskenderun).

Cilician Armenia – or Kingdom of Armenia in Cilicia, sometimes erroneously called Lesser Armenia. From the twelfth century over a period of 300 years this area was ruled by Armenian princes and kings.

Constantinople – Capital of the Byzantine Empire and one of the centres of learning in antiquity, renamed Istanbul by the Ottoman Turks. The Armenians shortened the name to ‘Polis’.

East Armenia – Part of Greater Armenia, which is situated to the north and northeast of Mount Ararat, where the present-day Republic of Armenia can be found.

Eastern Anatolia – Name erroneously given to the Armenian Highlands, region located to the east of Anatolia.

Erevan – see Yerevan.

Euphrates or Eufrates – A river flowing from the western side of the Armenian Highlands southward through Kurdistan and Iraq into the Persian Gulf, being one of the rivers of Eden.

Fra Mauro (1400-1464) – Venetian monk and cartographer, who, in 1459 made a giant World Map for the Spaniards. It contains detailed information – in Latin. On the map the name Karabakh is mentioned for the first time in western cartography.

Georgia – In this volume the name refers to the Caucasian Georgia. A country on the eastern shores of the Black Sea, which is the combination of historic countries of Iberia, Colchis, Mingrelia, etc.

Greater Armenia – see Armenia.

Hyrcanian Sea – see Caspian Sea.

Iberia – In this volume used mainly to denote Caucasian Iberia, which is the western part oftoday’s Caucasian Georgia.

Istanbul – see Constantinople.

Lesser Armenia – see Armenia.

Lesser Media — the northern region of Media, a part of the Iranian Empire, which coincides with the area of present-day Atrpatakan province of Iran, renamed Atropaten. See the explanation of Azerbaijan.

Masis – The Armenian name for Ararat (qv).

Mede or Media – A kingdom that existed since the first millennium BCE, in the north-western part of the Persian Plateau. The country of the Medes, who established a powerful empire.

Minsk Group or OSCE Minsk Group – Political group of western and Russian diplomats, who were given the task of resolving the question of Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh) by peaceful means. The group was created in 1992 by the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE).

Ottoman Empire – Successor empire to that of the Seljuk Turks, who had occupied the area of Asia Minor in the eleventh century. The Ottoman (Turkish) Empire expanded from Bursa to the Balkans, extending it over a wide territory. Established in 1453, dissolved in 1923.

Parthia or Perse or Pars – The old name of Persia, now Iran.

Persia – Country, now called Iran.

Ptolemy, Claudius (around 100-170 CE) – the greatest Greek cartographer who came from Alexandria, whose described methods of surveying were used for more than 1500 years. He is the author of the first atlas, entitled Geographia, which included maps.

Shirvan – The name of one of the main regions which lie inside the present day Republicof Azerbaijan. See also Azerbaijan.

Strabo (c. 63 BCE-24 CE) – Greek geographer, whose most important work, Geography has seventeen volumes, where 60 pages are allocated to Armenia and the Armenians.

Talish – Name of one of the regions and peoples which lie inside the present-day Republic of Azerbaijan and Iran.

Tigran II or Tigran the Great (ruled 95–55 BC) — An Armenian king who conquered the lands from the Caspian Sea to the eastern Mediterranean, including Mesopotamia, Syria and Cilicia.

Tigranocerta or Tigranakert – One of the ancient capitals of Armenia; probably the site of present-day Silvan, in Turkey. Recently a second fortress city named Tigranakert was discovered in eastern Artsakh (Karabakh). See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tigranakert_of_Artsakh

Toshpa or Tushpa – see Van.

Turcomania – A name given to Armenia by the Ottoman Turks. Also sometimes used in some western cartography around the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries,having been derived from the combination of the words Turkey and Armenia.

Turkey – The country that is now situated in and to the east of Asia Minor. The heirs to the Ottoman Empire.

Van – City, one of the oldest capitals of Armenia, situated to the east of Lake Van in the ArmenianHighlands. In ancient times it was called Toshpa, Tushpa, Thospitis.

Vilayet – Province of the Ottoman Empire.

West Armenia – Main part of Armenia, situated on the Armenian Highlands. This includes Greater Armenia to the southwest of Ararat and Lesser Armenia, including the area now occupied by the present-day Republic of Armenia.

Yerevan – Capital of present day Armenia. In Russian – Erivan, Persian – Iravan, in antiquity – Erebouni. It is one of the oldest towns having been continuously inhabited since Urartian times, for over 2800 years.

Suggested Reading

Alekbarli, Aziz – The Monuments of Western Azerbaijan. Ministry of Culture & Tourism, Baku, 2007

Ermolov, Corporal – Opisanie Karabagskogo Provincii v 1823 god. Tbilisi, 1866

Galichian Rouben – Historic Maps of Armenia. IB Tauris, London, 2004

____________________ – Countries South of the Caucasus in Medieval Maps. Komitas Inst., London 2007.

____________________ – The Invention of History, Komitas Inst., London, 2010

____________________ – Clash of Histories in the South Caucasus. Bennett & Bloom, London, 2012

____________________ – Armenia, Azerbaijan and Turkey, Addressing Paradoxes. Bennett & Bloom,

London, 2019.

____________________ – Borders of Armenia During 2600 Years of History. Zangak, Yerevan, 2022

Karapetian, Samvel – Armenian Cultural Monuments of the region of Karabakh. RAA, Yerevan, 2001

______________________ – The Microtoponyms of Artsakh. RAA, Yerevan, 2022.

Kortoshian, Raffi – The Endangered Christian/Armenian Heritage of Artsakh. RAA, Yerevan, 2022.

Strabo – Geography, Volume V. Loeb Classical Library, Harvard, 2000

Walker, Christopher – Armenia, a Very Brief History. Zangak, Yerevan. 2022, Third edition

_______________________ – Armenia Survival of a Nation. Croom & Helm, London, 1980 and 2000

www.tigranakert.am – Site of Tigranakert excavations and finds.

Mural on the southern wall of the Main church in Dadi Vanq Monastery, in Karabakh, dated 1297. Christ is on the left with Mother of God to the right of the image, which includes Armenian inscriptions. Inside back cover

Rouben Galichian (Galchian) was born in Tabriz, Iran, to a family of immigrant Armenians who had fled Van in 1915 to escape the Genocide, arriving in Iran via Armenia, Georgia and France. After attending school in Tehran Rouben received a scholarship to study in the UK and graduated with a Hon. Degree in Electronics Engineering from the University of Aston, Birmingham in 1963.

Rouben’s interest in geography and cartography started early in life, but he began seriously studying this subject in the 1970s. In 1981 he moved to London with his family, where he had access to a huge variety of cartographic material. His first book was entitled Historic Maps of Armenia: The Cartographic Heritage. The following year, an expanded version of the book (produced in Russian and Armenian) was published in Armenian.

Since then he has published eight more volumes, which could be seen on the front cover flap, most appearing in various language editions as well.

For his services to Armenian historical cartography Rouben was awarded an Honorary Doctorate by the National Academy of Sciences of Armenia in November of 2008. In 2009 he was the recipient of “Vazgen I” cultural achievements medal. In 2013 Rouben Galichian was awarded the medal of “Movses Khorenatsi” for outstanding achievements in the sphere of culture.

He is married and shares his time between London and mostly in Yerevan.

Book categories: Cartography, Culture, English, History, and Maps