KARABAGH (ARTSAKH) IN OLD MAPS

By Rouben Galichian – 2018

1 – GENERAL

In this article, the author will attempt to present a balanced, unbiased historic and cartographic view to the reader interested in enhancing their knowledge of how and when the historically Armenian–populated region of Karabagh (Artsakh – in Armenian) was described by various world-famous geographers and depicted by famed cartographers. For this reason, maps reproduced in the article (with the exception of the first image and the first map) are selected from the works of non-Armenian geographers and cartographers, whose maps form the basis of the world cartographic heritage. These documents have been sourced from various libraries across the world.

The documents discussed are in no way exhaustive, representing merely a small portion of the maps where Karabagh has been shown and named. Furthermore, the article excludes all descriptions and details mentioned in the travelogues of Islamic and Western travellers, who have chronicled their passage through Karabagh. These include Clavijo, who travelled during 1405-1407, Schiltberger, who travelled from 1396 to c.1422, and many others who travelled through the South Caucasus from the fifteenth to nineteenth centuries. These sources confirm the Armenian presence in the area by providing extensive detail about the population and their way of life in the region concerned. However, as they do not contain any maps, they have been excluded from this study.

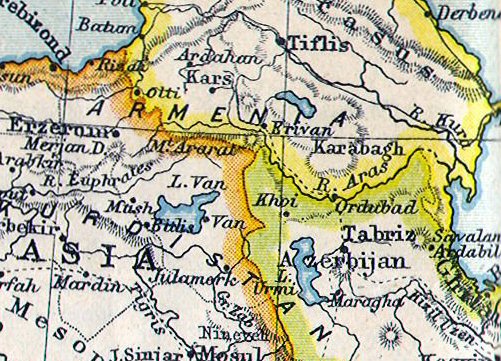

The maps come to prove that Karabagh or (in Armenian) Artsakh, has appeared in maps from around 1460. However, this does not imply that the name has been absent from older writings and documents, the discussion of which is outside the scope of this article (see Figure 1).

2 – EARLY AGES

The oldest cartographic or geographic information has reached us from the Greco-Roman sources, but these do not contain any documents which may be considered as maps. In the main, they constitute descriptive texts and references to mapmaking and maps prepared by some of the ancient geographers such a Hecataeus of Miletus amongst others. The maps alluded to in these works could today be seen in reconstructions only, prepared by celebrated cartographic experts such as Karl Müller, Konrad Miller, E.H. Bunbury, John Murray and others, based on the descriptions provided in the texts of ancient historians such as Hecataeus, Herodotus, Eratosthenes, Strabo and others. Today, when we refer to world maps of the Greco-Roman periods, we mainly refer to the reconstructions prepared by these specialists.

Interestingly, although these texts and maps contain names of countries, no borders are delineated. Generally speaking, regions, or as some prefer to call them “countries”, are labelled in accordance with the names of the races, peoples and nations who, at the time, inhabited the given area. Borders, given their artificial nature, are amorphous and transitory, rendering their depiction irrelevant, unless formed by major geological features, such as large rivers, lakes, seas and mountain ranges. Since the population of the region of Karabagh was mainly Armenian, the region was covered under the umbrella nomenclature of Armenia. On many maps the same name “Armenia” also appeared over the region of Karabagh-Artsakh. This said, names of regions generally do not appear in ancient and early medieval maps.

One of the founding fathers of cartography was ClaudiusPtolomaeus, known simply as Ptolemy (c. 90-168 C.E.) whose opus magnum, Geographia, is considered to be the most significant seminal work on geography and cartography. The book contains instructions on how to observe the universe, measure distances and angles, and general instructions on map preparation. His methods were so advances that they were used well into the sixteenth century. The book has a list of about 8,000 toponyms, divided by continents and subdivided into countries. Out of these toponyms, around 176 relate to Armenia Maior and Armenia Minor. No original map of the work has survived and the oldest manuscript copy of the work containing maps mentioned in the book to reach us dates from the thirteenth century. This contains the reworking of the drawings as mentioned by Ptolemy in his book.

On the maps redrawn according to Ptolemy’s descriptions and coordinates, countries are divided predominantly in accordance with natural topographical features, which did not always correspond exactly with existing borders, while few other maps of the ancient and early medieval periods show country borders at all. In Europe the tradition of omitting borders extended well into the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. In some medieval maps straight lines are drawn to artificially divide and/or specify countries, mainly as a visual aid. The map-maker was often unaware of the regions and countries he was drawing and had no knowledge of the strategic variations in their political geography and shifting borders; the option of omitting borders altogether remained, therefore, the safest. With the exception of the reconstructed and copied Ptolemaic maps, dating from around the fifteenth century, the practice of drawing borders came into use during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

3 –PRESENCE OF KARABAGH IN THE REGION

In keeping with the above–mentioned methodology of the Middle Ages, the name of the region of Karabagh (the Armenian Artsakh) did not feature in early maps, as it was considered to be a part of the country of Armenia or the Armenian population of the region, thus covered by the broader toponym of “Armenia”.

Notwithstanding the above, the name of Karabagh appears sporadically in maps prepared earlier than the sixteenth century. In such cases, the reference is invariably to the region between the Arax and Kura rivers located to the west of the confluence of the two, extending to the eastern end of Lake Sevan in Armenia proper. Up to the fourth century the country located east of Karabagh and north of the river Kura was named “Caucasian Albania” or in Arabic and Persian “Aran” – in Armenian “Aghvanq”. After the takeover of the region by the Iranian Sassanid dynasty during the late fourth century, Sassanid administrators combined the regions north and south of the Kura into one province, that of the Iranian Satrapy of Aran. For this same reason in Islamic cartography the region north of the Arax River, up to Mount Ararat, is sometimes referred to as Aran.

It must be mentioned that in all the Islamic maps of the ninth to twelfth centuries, the Iranian- Sassanid province of Aran also included the entirety of Georgia. Furthermore, north of the eastern end of the River Arax there was no country mentioned other than Aran. In all the Islamic maps Azerbaijan is shown south of the Arax, as a north-western province of Iran, its name having changed from Lesser Media to Atropatene during the second century B.C.E., a name, which itself evolved to Atorpaten, Adherbigan, Adherbaygan and finally, during the Arab and Turkish rules, to Azerbaijan. In all Islamic maps of the south Caucasus, there is a third country, Armenia, straddling the Arax River and extending south-westward to Bitlis, Amid and Miafarqin (old Armenian capital of Tigranakert, today near Diyarbakir, Turkey). Thus, it could reasonably be deduced that the region of Karabagh, north of the River Arax, has never been placed inside a country named Azerbaijan, as claimed by the present authorities of the Republic of Azerbaijan, since, prior to 1918, such a country did not exist in the region north of the Arax River. Azerbaijan, as name of a country, had always been a province of Iran, located south of the Arax River. Various Russian, British, Turkish, American and European encyclopaedias published before 1918 bear evidence to this fact.

Further scrutiny of maps of the region prepared by various renowned cartographers and published all over the world, confirms that north of the Arax there has never existed a country named Azerbaijan prior to 1918. The name of the region in medieval times was Aran, and after the Islamization of the majority of the population of this region, Karabagh and Aran were divided into smaller regions, where Muslim khans and beglarbeys ruled under the appellations of the khanates of Ganja, Shaki, Talish, Derbend, Shamakhi, Shushi etc., collectively given the all-encompassing name of Shirvan. Historically, in this area lived and ruled the five Armenian “Meliks” (derived from the Persian word “malek”, denoting large landowning families). These were quasi-independent rulers, though paid their tribute to whichever Persian or Ottomans overlord under whose suzerainty they found themselves during any particular period.

4 – KARABAGH IN OLD MAPS

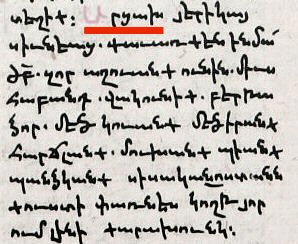

In medieval texts the name of Karabagh or Artsakh was mentioned in certain manuscripts, particularly in the first Armenian language geography book, the seventh century Ashkharhatsuyts (World Mirror) of Anania Shirakatsi, a paragraph from which can be seen in the detail from manuscript page of the work reproduced in Fig. 01, taken from MS N.1486- f102, in Matenadaran, Yerevan, dated 1597. In this extract from the page, the name Artsakh (Karabagh) is underlined red.

Historically Artsakh has been one of the fifteen provinces of medieval Armenia. The abovementioned book has extensive information about the provinces, including their location and important towns and villages, as well as a mileage chart for the region.

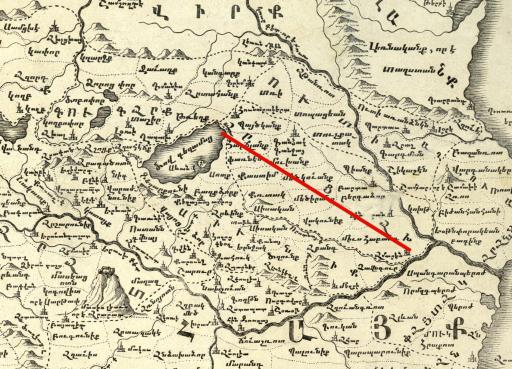

In a map prepared as per the descriptions of Anania Shirakatsi’s Ashkharhatsuyts, and published in Venice in 1751, the region of Artsakh lies near the confluence of the Arax and Kura Rivers. The image in Fig. 02 is a detail from this map entitled Armenia according to old and new Geographers, showing the region of Artsakh, underlined red.

Fig. 01- A paragraph related to Artsakh (underlined red) from a manuscript copy of the “Ashkharhatsuyts”.

Fig. 02 – Detail of Artsakh from the “Map of Armenia”, Venice, 1751.

* * *

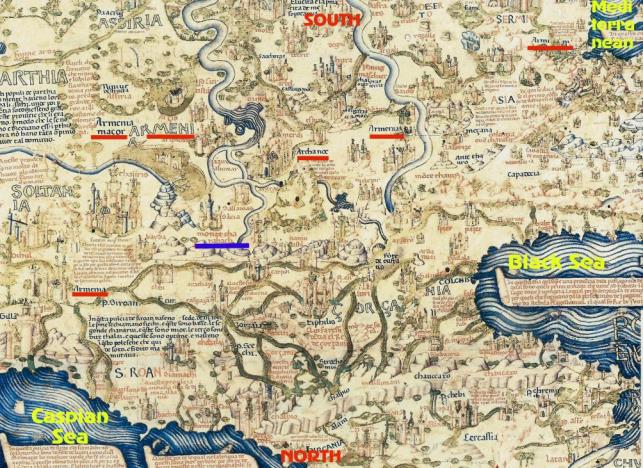

In western cartography, the name of Karabagh does not appear until the middle of the fifteenth century. In 1459, a World Map was commissioned by Portugal’s King Alfonso V. This huge map (two metres in diameter) was prepared by the Venetian cartographer Fra Mauro (c. 1400-1464). The original of the map was lost in transit from Venice to Portugal and a second copy was made by the master’s assistants and eventually sent to the king in 1460.

This map is oriented with the north at the bottom and, rather peculiarly for the epoch, shows an approximately correctly shaped Caspian Sea, which on other maps, prepared well into the 1700s, is shown in its traditionally accepted flat oval form. The detail map of Fig. 03 shows the region of Armenia in Fra Mauro’s work, with the toponym Armenia underlined red. On the lower left part of the map Armenia is mentioned near the confluence of the two rivers Arax and Kura. Another Armenia in black letters and ARMENIA in gold letters appear at towards the top left of the map with the Iranian Azerbaijani city of Thauris (Tabriz) to their south (above). Near these toponyms other cities such as Choi (Khoy), Carpi and Aragats are also indicated. These are cities in or near the region of Armenia. To the right of ARMENIA, on the other side of the river, the pile of stones depicts Mount Ararat with Archa Noe (Noah’s Ark) sitting on the summit. Between these two the name of the Armenian city of Salmas[t] and the Artsakh town of Barda are shown, with Monte Charabach (Mountains of Karabagh) in-between, underlined blue. Here, for the first time in Western cartography, the name of Karabagh is mentioned. Below the confluence of Arax and Kura the toponym Siroan (Shirvan) can be seen, a name given to the region corresponding to the location of the present-day Republic of Azerbaijan.

Fig. 03 – Detail from Fra Mauro’s “Mappa Mundi”, 1460, Venice.

* * *

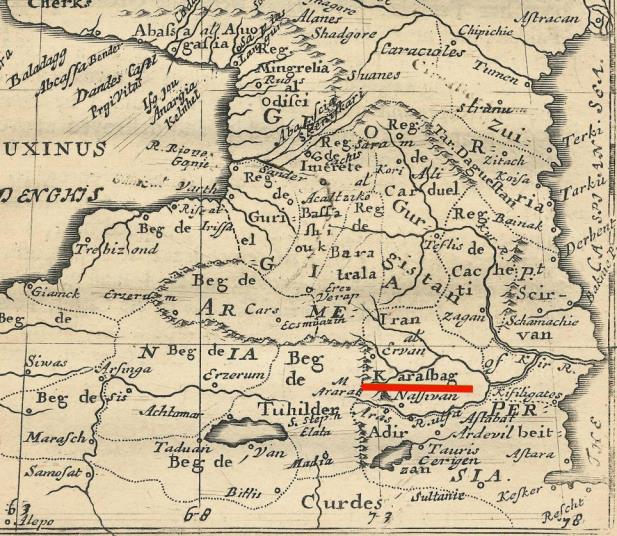

Fig. 04 – Detail from the map of “Asia” by Mercator, published in Duisburg in 1595 by his son Rumold.

Gerardus Mercator (1512-1594) was one of the most important Flemish cartographers of the time, and his projections for showing the spherical earth on a flat sheet of paper are widely used even today. His atlas of the world was published posthumously by his son Rumold and contains many detailed maps of Europe and beyond.

The detail image shown in Fig. 04 is taken from Mercator’s Map of Asia. The western part of Armenia appears here as Turcomania (Turkish-Armenia) as being a part located in the region under

the Ottoman rule, while eastern Armenia is shown under Persian domination. The region north of Armenia, neighbouring the Mare di Sala olim Caspium (Caspian Sea), is named Seruan (Shirvan), while the Persian cities of Merent (Marand) and Coy (Khoy) are placed south of the River Arax flowing into the Caspian. North of the Arax, the name Carabach could be seen underlined red. The Armenian populated cities of Van, Mus[h] and Vastan are indicated inside the Armenian territory occupied by the Ottoman Empire.

* * *

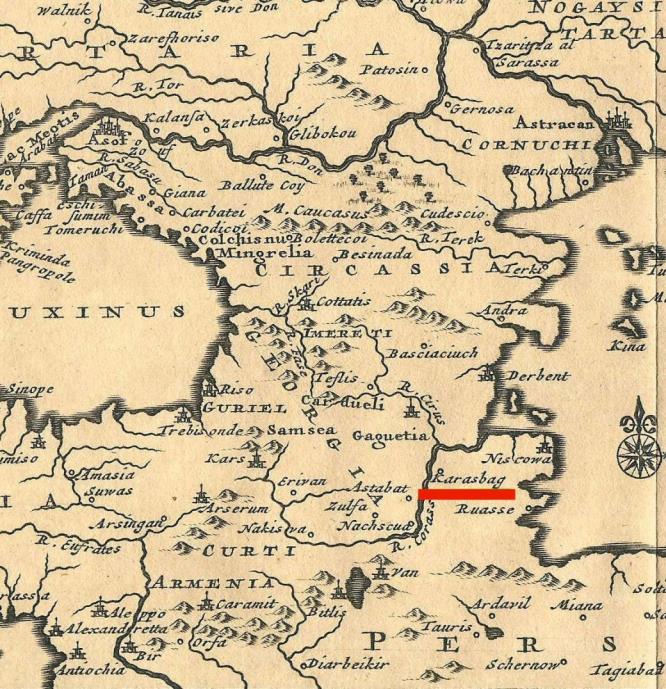

The Royal Geographer Philip du Val (1619-1683) was an important French cartographer. Fig. 05 shows a detail from his map of Turkey in Asia published in 1676, where the green line delineates the border of the Ottoman and Persian Empires. Western Armenia is under Ottoman rule and here entitled Turcomanie al. Armenie (Turcomania or Armenia, see endnote xiv), which includes the region of Nachijevan and Ararat, as well as the cities of Kars, Erivan, Van etc.

Fig. 05 – Detail from the map of “Turkey in Asia” by du Val, dated 1676, showing the border of the Ottoman and Persian empires.

The adjoining territory to the east, inside Persia, include the provinces of Adherbetzhan (Azerbaijan) and Kilan (Gilan). The cities of Tauris, Chui, Ardebil, Maraga and others are placed inside the Iranian province of Azerbaijan. The Persian–occupied territory in South Caucasus extends northward up to Shirvan and Derbend.

On this map, the region north of the rivers Arais (Arax) and Kur are named Shamachie and Shirwan, but the triangle inside the confluence of the rivers Kura and Arax is entitled Karasbag (Karabagh), underlined red.

* * *

The British cartographer Robert Morden’s (1668-1703) atlas entitled Geography Rectified contains a map called Armenia, Georgia and Comania. Here the borders between the Ottoman and Persian empires are shown broadly in line with du Val’s work. This map is reproduced in Fig. 06, where Scirvan (Shirvan) and Shamachie are placed north of the Aras and Kur Rivers inside the Persian Empire, while Karasbag (Karabagh underlined red) with Nassivan (Nakhijevan) are placed west of the confluence of the rivers, inside the Persian–occupied territory north of the Arax.

Fig. 06 – Part of the map of “Armenia, Georgia and Comania” by Morden, 1700, the imsge shown may possibly be a later revision.

* * *

The Dutch cartographer Pieter Van der Aa (1659-1733) published his Atlas Nouveau et Curieux around 1710, which contained a map of the Tartar territories. A detail from this map is reproduced in Fig. 07, showing the regions of Caucasus extending to northern Persia. It covers the regions of Circassia, Georgia, Armenia and Persia. Here Karasbagh, underlined red, is shown on the southern shore of the river Corasse (Arax) and Cirus (Kura), north-east of Nachsua (Nachijevan) and north of Ardavil (Ardabil) located inside Persia. The map does not include political boundaries.

Fig. 07 – Detail from the “Tartarie” map of van der AA.

* * *

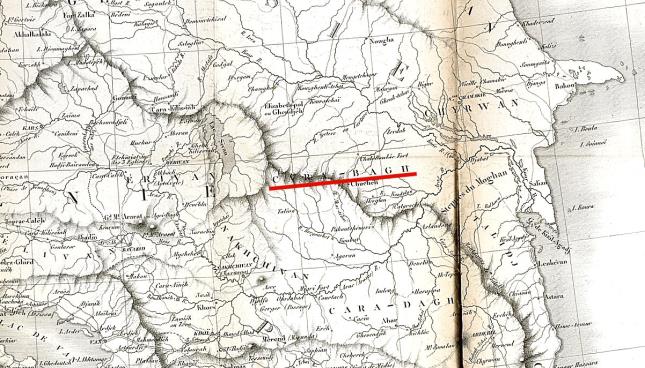

Pierre Amédée Jaubert (1779-1847) began his travels through Turkey and Armenia towards Persia in 1805. After spending four months in the Turkish town of Bayazed, where he was imprisoned by the Pasha, Jaubert was allowed to continue his journey only after the Pasha’s death. In his book, Voyage en Arménie et en Perse (Paris, 1821) he writes about his experiences and includes a map of his travelled route, drawn by the well-known French cartographer Pierre Lapie (1777-1850).

The detail reproduced in Fig. 08 from Lapie’s map, shows the region of southern Caucasus. North of the Kura, where we can see the territories of Chyrwan (Shirvan) and Talidj (Talish). These are the main areas today incorporating the Republic of Azerbaijan.

Here Cara-Bagh, underlined red, is placed between the rivers Araxes and Kour, east of the Lake Sivan (Sevan) and south of Elizabethpol or Ghandjeh. On the map the sister territory to Karabagh, namely that of Cara-Dag, is shown south of the Arax, inside the territory or Persian Azerbaijan.

Fig. 08- Detail from Lapie’s map showing the route taken by Jaubert, when travelling from Constantinople to Persia in 1805.

* * *

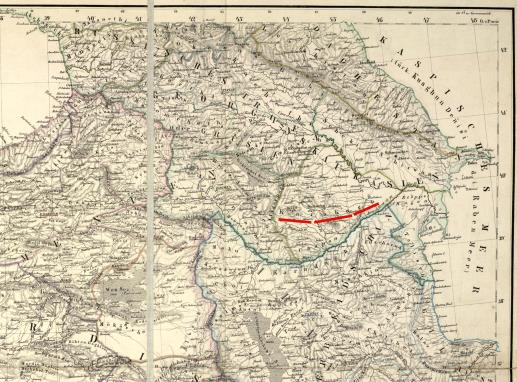

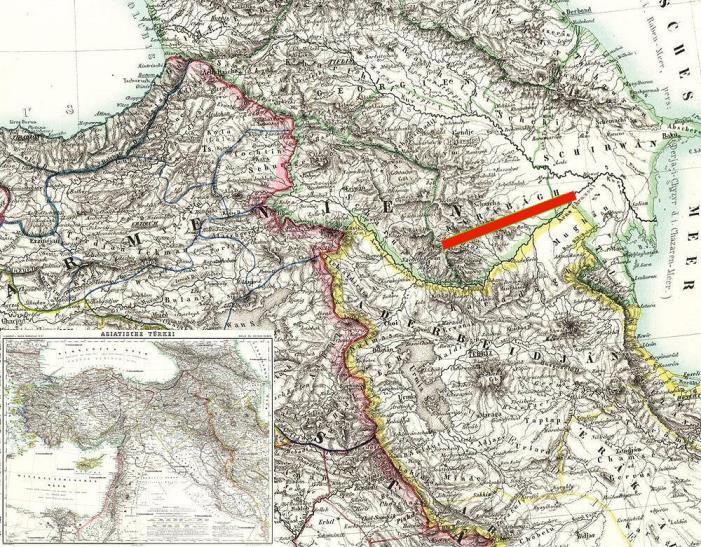

Heinrich Kiepert (1818-1899) was a German cartographer, who spent most of his working life in the South Caucasus and eastern part of the Ottoman Empire. His maps of the Ottoman Empire, Armenia, the Iranian province of Azerbaijan and Georgia are celebrated for their detail and accuracy. The map of Fig. 09 is taken from his map of the Ottoman Empire, 1844, published in Germany. Its Ottoman Turkish translation was published in 1854.

South of the Arax River we see the Persian Province of Azerbaijan and to its north lie the regions of Chapan (Kapan) and Karabagh, underlined red The latter extends from the confluence of the Aras and Kur to the east of Lake Goktgchai or Sewanga (Lake Sevan), including the town of Schusha (Shushi in Karabagh).

Fig. 09 – Easternmost part of Kiepert’s map of the “Ottoman Empire”, 1844.

* * *

Fig. 10 – Detail from one of the maps of the first Armenian Atlas, published in 1849.

The map of Fig. 10 pn the previous page, is one of the maps of the first Armenian Atlas, printed (in the Armenian language) in Venice in 1849 and entitled The World according to the Old and New Geographers of France, England, Germany and Russia. The detail reproduced here is from its section entitled The Ottoman Empire. It covers the eastern end of the Ottoman Empire, western edge of Persia and south of the Caucasus.

Here, Azerbaijan can be found south of the Arax River, inside the Persian Empire, while across the river, to the north of the river, we see Armenia with its easternmost region, Karabagh, underlined red placed at the confluence of Arax with Kura.

* * *

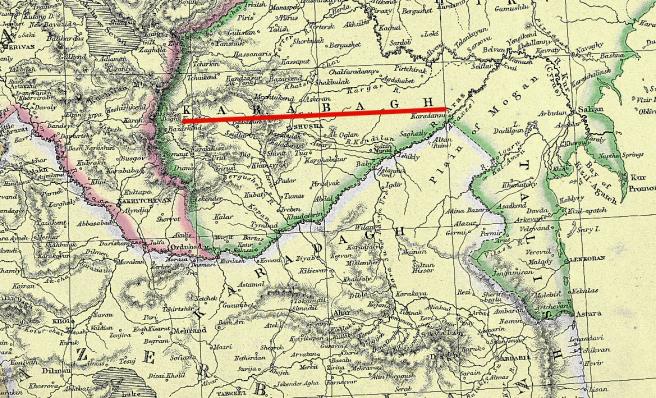

The next detail is from the map of the Caucasus and Armenia by the British cartographer Edward Weller (1819-1884) another cartographer, whose maps were lauded for their accuracy. The map reproduced in Fig. 11 depicts the border of the Persian and Russian Empires from Wellers’ map of 1858 entitled The Isthmus of Caucasus and Armenia.

Weller shows Azerbaijan as a province of Persia, with the region of Karadagh on the southern bank of the River Aras(x), while Karabagh is on its northern bank, extending from east of Lake Sevan to the confluence of the rivers Aras and Kur (Cyrus), underlined red. To the north of Karabagh lie the southern Caucasian regions of Shirvan and Sheki, which in 1918 were absorbed in the newly founded country of Azerbaijan.

Fig. 11 – Detail of the border of Iran and Russia from Wellers’ map of the “The Isthmus of Caucasus and Armenia”, 1858. London.

* * *

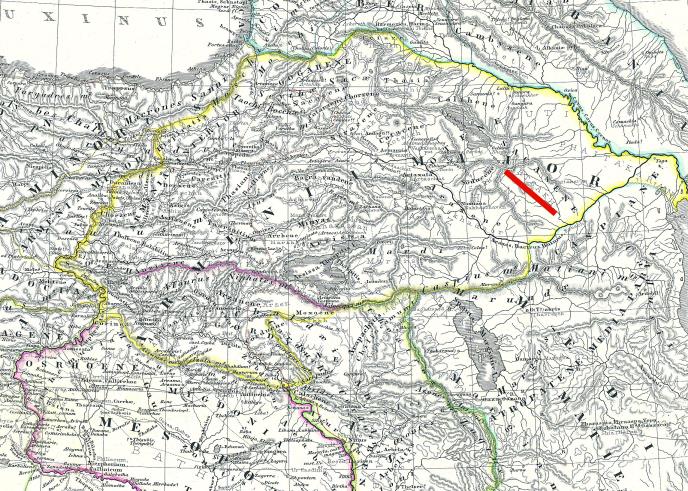

Fig. 12 is a partial section from the map of the old–world specialist German cartographer Karl Spruner (1803-1892), famed for his many beautiful and detailed maps and atlases of the old world. This particular work is taken from Spruner’s 1855 Atlas Antiquus and is entitled Armenia, Mesopotamia, Babilonia et Assyria.

On the map, the provinces of Armenia are delineated and named both in Latin and Armenian, in keeping with their appellation in the Middle Ages. The province west of the confluence of the Araxes and Cyrus rivers appears as Sacasene and/or Artsakh, underlined red and extending westward to Siunik.

Fig. 12 – Detail from Spruner’s map of the ancient lands entitled “Armenia, Mesopotamia, Babilonia et Assyria”, 1855.

As this is a map of the area in ancient times, the Persian province south of the Araxes still appears in accordance with its ancient nomenclature of Mediene (Media), which, as mentioned earlier, was later changed to Atropatene, in honour of the military commander of the region Atropat. This region is today known as the Iranian province of Azerbaijan, while the Armenians still call it by its ancient name “Atrpatakan”. The present-day Republic of Azerbaijan was established on the northern shores of the Arax River, borrowing its name from the Persian province, located south of the river.

* * *

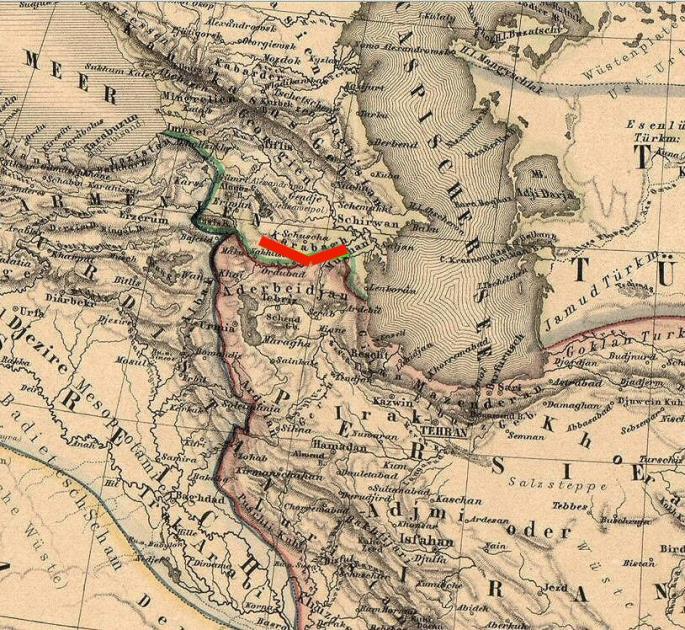

Fig. 13 – Detail from Adolf Graf’s map entitled “SüdwestAsien”, Weimar, 1866.

The map of Fig. 13 is a work prepared by the German Adolf Graf in 1866 and published by the Weimar Geographic Institute. It shows the south-western part of Asia, where Armenia is shown divided between the Ottoman and Russian Empires This reflects the situation after the war with Persia and the treaties of Gulistan and Turkmenchai (1813 and 1828), whereby the Persian–conquered territories of the South Caucasus were taken over by the Russian Empire.

Aderbeidjan (Azerbaijan) is shown south of the Arax River, while further north the region inside Russian–occupied territory is named Karabagh, underlined red. To its north is the region, which, since 1918 is home of the Republic of Azerbaijan, and here is entitled Schirvan, a general name given to these regions.

* * *

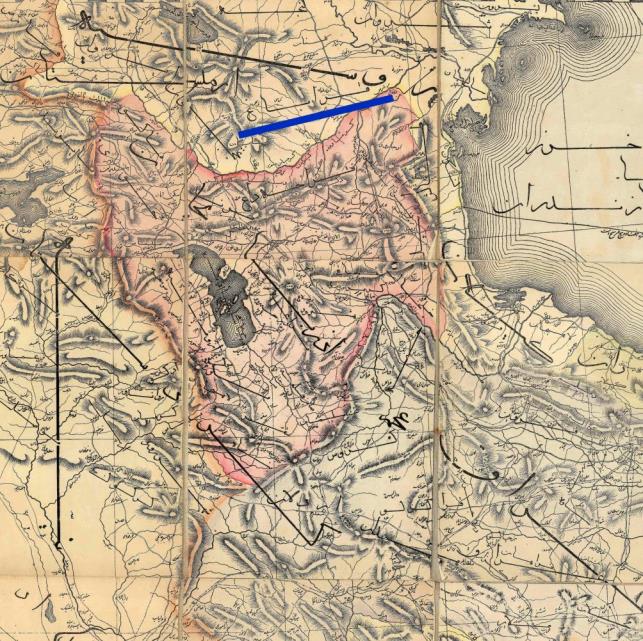

Fig. 14 – North-western part of Qarachedaghi’s “The Map of All the Countries under the Protection of the Iranian Government”, 1869.

The first printed map in Persian was that entitled The Map of All the Countries under the Protection of the Iranian Government, published in 1869. This was in fact the map of ancient Persia, prepared by the Iranian cartographer Qarachedaghi, one of the pioneers of cartography in Iran. Fig. 14 is the north-western region of Iran from this map.

Here, the names appearing in the border regions between the Russian Caucasus and Iran are self-explanatory. Inside Iranian territory, the border province (outlined in pink) is named Azerbaijan. One of its regions, on the southern shore of the Aras River (Arax) is Karadagh. Consistent with all other maps, the neighbouring Russian–occupied region north of the river is named Karabagh, underlined red, with the Shirvan to its east, Nakhijevan to its south and Irevan (Yerevan) to its west.

* * *

Fig. 15 – British map entitled “Turkey in Asia, Arabia, Persia, Afghanistan & Baluchistan”, 1900.

The map of Fig. 15 is a British map from 1900 entitled Turkey in Asia, Arabia, Persia, Afghanistan & Baluchistan. On this detail taken from the map the border of Persia and Russia shows the situation of Southern Caucasus, which is exactly the same as it was in 1869, shown in Fig. 14 above.

In this map, Azerbaijan is a province of Iran, Karabagh, underlined red, lies north of Arax River and west of its confluence with Kura. The territory of Armenia is shown as divided between the Russian and Ottoman Empires.

* * *

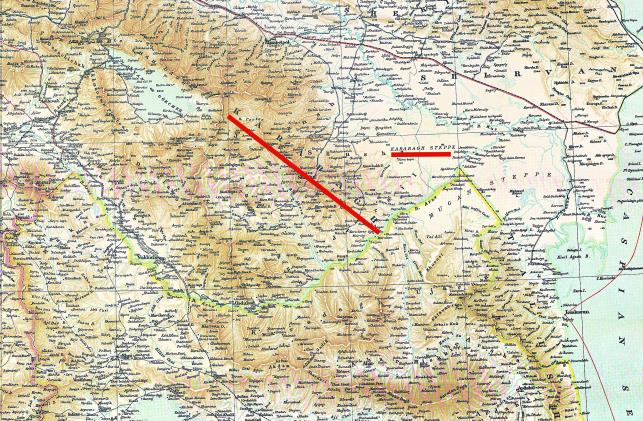

Henry Finnis Blosse Lynch (1862– 1913) was a British traveller, who spent time in western and eastern Armenia and his two-volume illustrated work entitled Armenia, Travels and Studies is a detailed description of the land and peoples of Eastern (Russian provinces- Vol. I) and Western (Turkish province, Vol. II) Armenia. The volumes are accompanied by a detailed map entitled Map of Armenia and Adjacent Countries, 1901, as well as numerous images and sketches. The detail shown in Fig. 16 is taken from Lynch’s map.

In this map Karabagh is shown extending from the south-eastern end of Lake Sevan eastward to the Karabagh Steppe. This is the name given to the easternmost region inside the confluence of the rivers Arax and Kur, at the time under the rule of the Russian Empire. The name of this region is underlined red.

Fig. 16 – Part of Lynch’s “Map of Armenia and Adjacent Countries”, 1901.

* * *

Fig. 17 is a detail from the General Map of the Theatre of the Turkish War, published 1916 in Berlin by Dietrich Reimer, which was based on Kiepert’s Map of the European and Asian Provinces of the Ottoman Empire. The section reproduced is that of the region of South Caucasus.

Fig. 17 – Detail form “Theatre of the Turkish War” in 1916 by Kiepert, D. Reimer. Berlin.

North of the Aras River [Arax], inside the Russian borders, the region from Lake Sevan to the confluence of Arax and Kour rivers is indicated as Karabagh, underlined red. In the north it is bordered by Shirwan and to the west it reaches the area of Zangadzor (Zangezur) in Syunik, Armenia.

* * *

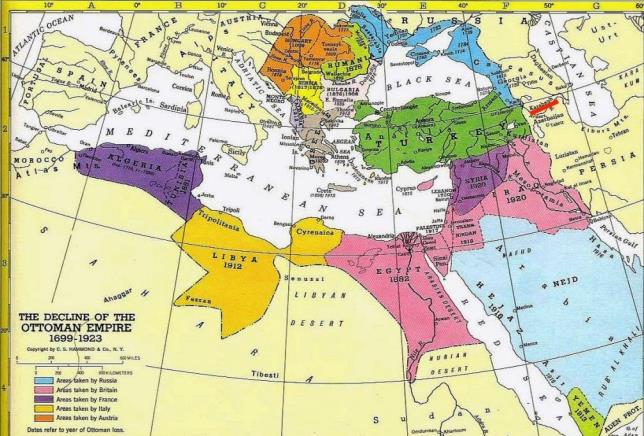

The final map of the article, Fig. 18 is a work by Hammonds dated 1923. It shows the territories of the Ottoman Empire prior to its demise and fragmentation.. Here, Karabagh lies outside the borders of the Empire, directly to its east and is placed north of the Arax River, while the territory south of the river, inside Iran, is named Azerbaijan. Karabagh is underlined red.

Fig. 18 –Hammonds map of the Ottoman Empire in 1923. Karabagh lies outside the Empire.

* * *

From the analysis of the above maps and all other relevant documents one could conclude that the predominantly Armenian–populated region of Karabagh/Artsakh has been present on the maps prepared by (non-Armenian) mainly western specialists since the 1460s. In all maps of the region which include details and their toponyms, the name of Karabagh is omnipresent. Regarding the population of Karabagh, all travelogues confirm that the region has been populated by Armenians. To cite one example, Schiltberger, who spend 26 years with Tamarlane and his son Shahrokh, writes the following in his memoirs entitled Of Bondage and Travels, 1396 to 1427:

I have also been a great deal in Armenia. After Tämurlin [Tamarlane] died, I came to his son, who has two kingdoms in Armenia. He was named Scharoch [Shahrokh]; he liked to be in Armenia, because there is a very beautiful plain. He remained there in the winter with his people, because there was good pasturage. A great river runs through the plain is called the Chur [Kura], …… and near this river, in this same country, is the best silk. The Infidels [Muslims] call the plain in the Infidel tongue Karawag [Karabagh]. The Infidels possess it all, and yet it stands in Ermenia. There are also Armenians in the villages, but they must pay tribute to the Infidels. I always lived with the Armenians, because they are very friendly to the Germans and because I was a German they treated me very kindly; and they also taught me their Pater Noster…

The above is given as an example and will be subject of another research and article.

* * *

APPENDIX

The reader is reminded of the author’s suggestion, supported by Iranian and Armenian specialists, that the prefix “kara”, which in the Turkish and Azerbaijani languages means “black”, should be correctly translated as “great” or “big”. These names originate from the Middle Ages, when the language of the local population comprised dialects of the old Persian, the Pahlavi language. In these languages, the word kara or kala was used to denote “large” or “big”.

Accordingly, Karabagh, which is translated as “Black-garden” should be “Large garden” and similarly “Karadagh” should be translated to “Large Mountain”. These are more appropriate terms, as the first one is a forested and green country and the second is dominated by a mass of high mountains.

This correction will clarify why there are so many names with the prefix “kara” in Iranian Azerbaijan and Turkey with little relevance to the colour black. Further credence is lent to this assertion as follows:

- The largest tree in the city of Tabriz was called “Kara-aghaj“, meaning “Large tree”, not “Black tree”.

- One of my Azeri colleague’s tall and well-built great grandfather was, according to him, addressed as “Kara-agha”, meaning “Big sire” not “Black sire”.

- The widest river in Iranian Azerbaijan is called “Kara-su”, meaning “Large water” not Black water”.

- The largest monastery in Iranian province of Western Azerbaijan is St Thaddeus, constructed in white marble, with only one of the domes having two layers in black stone. This is called “Kara-Kilisse”, meaning “Large church” not “Black church”.

The author suggests that this matter is worthy of fuller investigation by competent authorities and specialists.

Rouben Galichian

Yerevan, 2018.

ENDNOTES

iDeClavijo,RuyGonzales. Narrative of the Embassyof theRuy Gonzales deClavijoto the Court ofTeimourat Samarkand. Transatedby Clemens Markham. London:Hakluyt Society, 1854.

ii SchiltbergerJohann. Bondageand Travels,1396 to 1427. TransletedbyTelferBuchan. London: Hakluyt Society, 1879.

iii Galichian,Rouben. Clash of Histories in the South Caucasus. London:Bennett & Bloom, 2012.92‐116.

iv Galichian, Rouben.Historic Maps of Armenia. London and New York:I .B.Tauris, 2004, 12.

v It must be noted that the earlies Ptolemaic maps date from the thirteenth century and most of the mainstream maps attributed to Ptolemy were drawn after the 1470’s, when the drawing of borders was already being practiced.

vi Galichian,Rouben. Countries Southof the Caucasus in Medieval Maps. London:GomidasInstitute,2007.45, 91,194‐196.

vii Ptolemy.Geogrpahia,prepared byLaurenzo Fries,Manuscript Maps. C.1.d.11 and other copies in the British Library.For full texts of towns etc. see also Galichian, Rouben.Historic Maps of Armenia.London and New York: IBTauris, 2004, 96‐99.

viiiGalichian, Rouben.Countries South of the Caucasus. Op.cit.94‐130.Here, the most important Islamic maps depicting the area are reproduced. These include the works of Istakhri, Ibn Hawqal, Idrissi, Qazwini, Mas’oudi, and Ibn Said.

ix For further historic and cartographic details related to the subject see Galichian, Rouben. The Invention of History. London:GomidasInstitute,2009/2010 and Galichian,Rouben. Clash of Histories in the South Caucasus. London:Bennett & Bloom,2012. Even Ottoman,Persian and Arab geographers and cartographers, never show a country named Azerbaijan north of the Arax River. Thecountry by this name appeared only in 1918 and contrary to its current claims of having three thousand years of history.

x Some experts are of the opinion that the author of theAshkharhatsuyts is the fifth century historiographer Movses Khorenatsi, the author of theHistory of the Armenians. However,this author is of the opinion that the book was penned byAnaniaShirakatsi, in the seventh century,as it contains references to sixth and seventh century European historians.

xi Fra Mauro’s map is kept in the BiblioteccaMarciana, Venice.

xii The correct shape of the Caspian Sea was not known until 1720s, when Peter the Great of Russia had it comprehensively surveyed. Until then the generally agreed shape was a flat oval, and in the ancient times was thought to be connected to the Northern Ocean. Itis a mystery how a fifteenth century cartographer would show the correct shape of the Caspian,onlysurveyed some 250 years after the making of his map.

xiiiThis could refer to MountAragatsor the region ofAragatsin Armenia.

xiv Fora period of a century or so, West Armenia, which was under the occupation of the Ottoman Empire, was on certain Western maps given the name ofTurcomania. At the same time in some of the atlases it is explained that “Turcomania and Turkish [West] Armenia are the same”. The name has possibly arisen from the more generally used terminology of “Turkish‐Armenia”, hence “Turco‐[Ar]mania”.

xv Galichian, Rouben. The Invention of History.Op.cit.,6‐12and 27‐31.

xviGalichian, Rouben.Clash of Histories in the South Caucasus.Op.cit., 103.

xvii Further details of the varioustravelers’writings can be found in Rouben Galichian’sClash of Histories in the SouthCaucasus,Op. cit.

xviiiKasravi, Ahmad.“Azeri,or the ancientl anguage of Azerbaijan”,Collection of 78 papers. Tehran:KetabhayeJibi, 2536 (Persian).See alsoAbdolaliKarang,TatiandHarzanitwo ancient dialects of Azerbaijan. Tabriz:Vaezpour, 1954(Persian).andBagrat Ulubabian,The Kingdom of Khachenin 10‐16th centuries. Yerevan: NAS1975,42‐43(Armenian).

xix Galichian,Rouben.HistoricMapsof Armenia. Op.cit., 210.